Many people think asthma and COPD are the same thing - both make you breathe hard, both involve wheezing, and both can land you in the hospital. But they’re not the same. In fact, mixing them up can lead to the wrong treatment, worse symptoms, and even dangerous outcomes. If you or someone you know is struggling with breathing problems, knowing the difference isn’t just helpful - it’s essential.

What’s Actually Happening in Your Lungs?

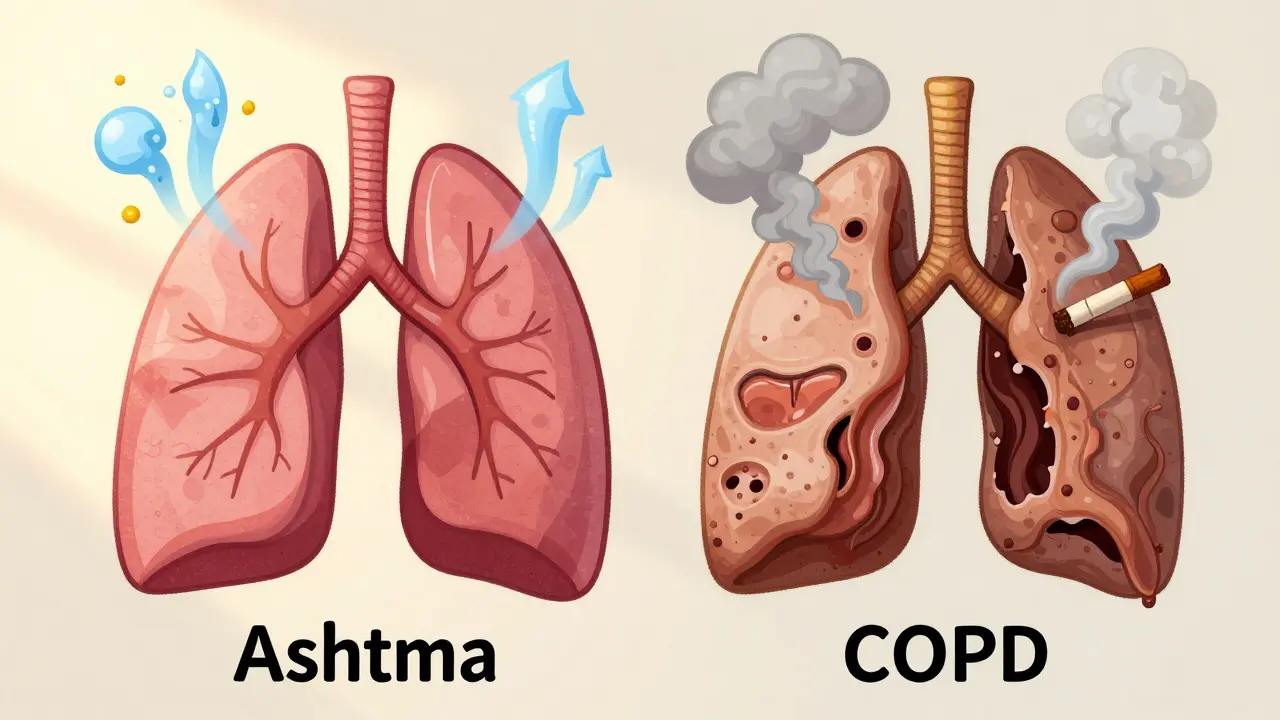

Asthma is an allergic, inflammatory condition. Your airways swell up and tighten when they react to triggers like pollen, cold air, or exercise. Between attacks, many people feel completely normal. The airway narrowing is usually reversible - with the right inhaler, you can get back to breathing easily.

COPD, on the other hand, is damage. It’s caused mostly by years of smoking or long-term exposure to pollutants. The air sacs in your lungs (alveoli) break down, or the airways get clogged with thick mucus. This damage doesn’t heal. Even with treatment, your lungs won’t go back to how they were. You’re not having flare-ups - you’re living with constant decline.

Symptoms: When It’s Asthma vs. When It’s COPD

Here’s how to tell them apart by what you feel:

- Asthma: Symptoms come and go. You might feel fine in the morning, then struggle to breathe after running or being around cats. Nighttime coughing or wheezing is common. The cough is usually dry - little to no phlegm.

- COPD: Symptoms are constant. You wake up with a cough that produces thick mucus - often called a "smoker’s cough." You’re always out of breath, even walking to the kitchen. By the time people notice, they’re already struggling to climb stairs. Cyanosis - blue lips or fingernails - shows up in advanced cases because your body isn’t getting enough oxygen.

One big clue? Age. Asthma usually starts before age 30. In fact, half of all cases are diagnosed by age 10. COPD almost never shows up before 40. Most patients are over 45, and nearly all have a history of smoking.

Diagnosis: What Tests Reveal

Doctors don’t guess. They test. The most common tool is spirometry - a simple breathing test that measures how much air you can blow out and how fast.

In asthma, your lung function improves by 12% or more after using a bronchodilator (like albuterol). That’s a clear sign your airways are just tight, not broken. About 95% of asthma patients show this reversibility.

In COPD, that improvement is minimal - usually less than 12%. Your lungs are damaged, not just inflamed. Another test, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), checks for inflammation. If your FeNO level is above 50 ppb, it’s likely asthma. Below 25 ppb? More likely COPD.

Blood tests for eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) also help. Levels above 300 cells/μL point to asthma or overlap syndrome. Below 100? That’s typical for pure COPD.

High-resolution CT scans show even more: 75% of COPD patients have visible lung damage (emphysema), while only 5% of asthma patients do.

Treatment: Different Tools for Different Problems

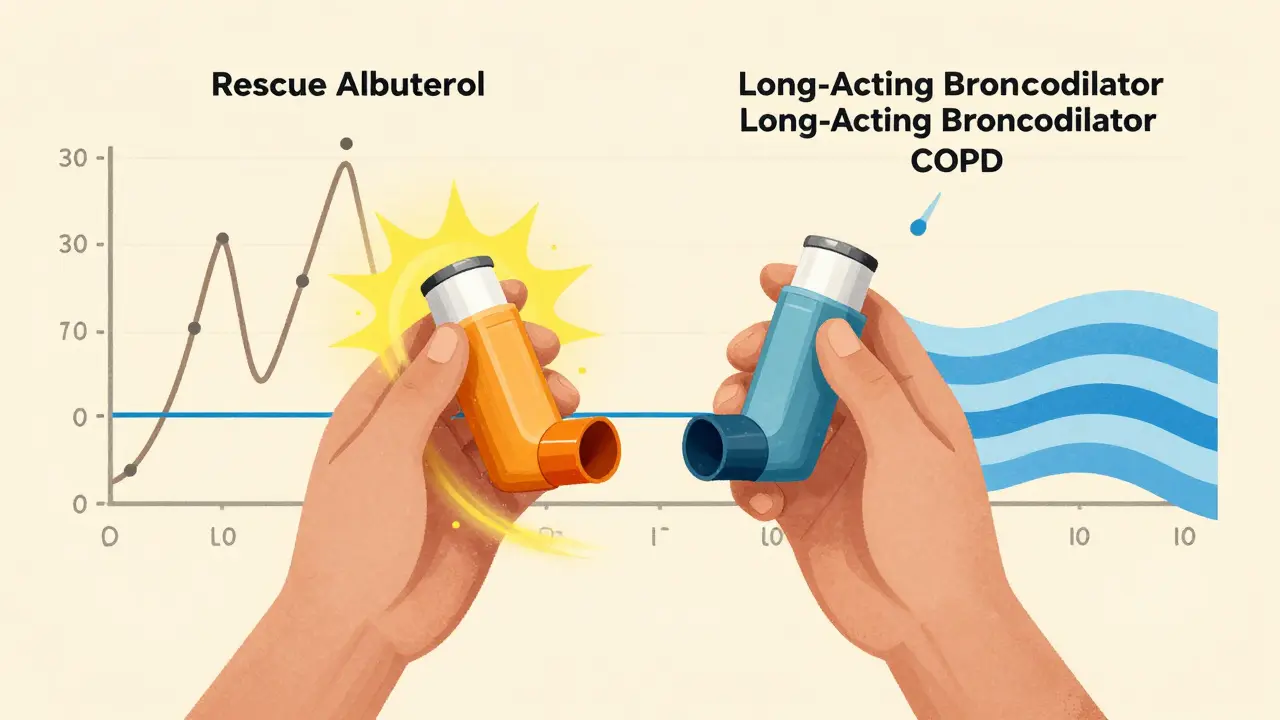

Asthma treatment is about control. You start with a rescue inhaler - usually albuterol - for sudden symptoms. If you’re having symptoms more than twice a week, you add an inhaled steroid to calm the inflammation. For severe cases, biologics like mepolizumab target specific immune cells causing the flare-ups. These drugs have changed lives for people with hard-to-control asthma.

COPD treatment is about slowing decline. Bronchodilators - long-acting ones (LABAs and LAMAs) - are the first line. They open the airways, but they don’t fix the damage. Steroids? Only added if you’re having frequent flare-ups. Oxygen therapy becomes necessary as the disease progresses. Pulmonary rehab - exercise, breathing training, education - helps COPD patients walk 54 meters farther on average. For asthma patients? Only 12 meters. Why? Because their baseline is usually good.

And smoking cessation? It’s non-negotiable in COPD. Quitting cuts disease progression by 50%. In asthma, smoking makes symptoms worse, but it’s rarely the root cause. Still, quitting helps everyone.

The Gray Area: Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS)

Not everyone fits neatly into one box. About 15-25% of people with obstructive lung disease have ACOS - a mix of both conditions. These patients often have a history of asthma since childhood, then started smoking later in life. They have eosinophilic inflammation (like asthma) but also fixed airflow blockage (like COPD).

ACOS is worse. These patients have 2.3 times more flare-ups than asthma alone and 1.7 times more than COPD alone. They end up in the ER more often - 1.8 times per year on average. Treatment usually means triple therapy: two long-acting bronchodilators plus an inhaled steroid. But evidence is still limited. This is the hardest group to treat, and misdiagnosis is common.

Prognosis: What to Expect Long-Term

Asthma has a strong outlook. With proper management, 89% of patients control their symptoms well. The 10-year survival rate for moderate asthma is 92%.

COPD is different. Even with treatment, only 52% report good symptom control. The 10-year survival rate for moderate COPD is 78%. And it’s the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S., killing about 152,000 people each year.

One twist: if you’ve had asthma for over 20 years, your airways can start to stiffen permanently. About 15-20% of long-term asthma patients develop fixed airflow limitation - making them look more like COPD patients. That’s why ongoing monitoring matters.

What You Can Do Now

If you’re wheezing or short of breath:

- Track your symptoms. When do they happen? After exercise? At night? After smoking?

- Write down your triggers. Dust? Pollen? Cold air? Smoke?

- Don’t ignore a chronic cough with mucus - especially if you’re over 40 and smoked.

- Ask for spirometry. It’s quick, cheap, and tells you more than any guess ever could.

- If you smoke, quit. No matter the diagnosis, it’s the single best thing you can do for your lungs.

Getting the right diagnosis isn’t about labels - it’s about getting the right treatment. The wrong inhaler won’t help. The wrong advice can make things worse. Take your symptoms seriously. See a doctor. Get tested. Your lungs are counting on it.

Can asthma turn into COPD?

Asthma doesn’t automatically turn into COPD. But if you’ve had asthma for decades - especially if you smoke - your airways can become permanently narrowed. This is called fixed airflow obstruction. About 15-20% of long-term asthma patients develop this, making their condition look like COPD. It’s not a transformation - it’s damage from uncontrolled inflammation and smoking.

Is COPD only caused by smoking?

Mostly, yes. About 90% of COPD cases are linked to cigarette smoking. But not all. Long-term exposure to air pollution, chemical fumes, or dust - especially in poorly ventilated workplaces - can also cause it. In rare cases, a genetic condition called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency leads to COPD even in non-smokers. Still, smoking is by far the biggest risk.

Can I use my asthma inhaler for COPD?

You can use a rescue inhaler like albuterol for sudden COPD symptoms - it helps open your airways. But it won’t stop the disease from getting worse. COPD needs long-acting bronchodilators (LABAs or LAMAs) for daily control. Adding steroids only helps if you’re having frequent flare-ups. Using only an asthma inhaler for COPD is like putting a bandage on a broken bone - it masks the problem, but doesn’t fix it.

Why do some people with asthma need biologics?

Biologics like omalizumab or mepolizumab are for severe asthma that doesn’t respond to standard inhalers. They target specific parts of the immune system - usually eosinophils or IgE - that drive inflammation. These drugs are used in about 5-10% of asthma patients, typically those with high eosinophil counts or allergic triggers. They’re not for COPD, because COPD isn’t driven by the same immune pathways.

How do I know if I have ACOS?

If you’ve had asthma since childhood, started smoking later, and now have constant breathing problems with frequent flare-ups, you might have ACOS. Doctors look for a mix: high eosinophil levels (like asthma) plus fixed airflow blockage on spirometry (like COPD). FeNO levels above 50 ppb and blood eosinophils above 300 cells/μL are red flags. If your symptoms are worse than expected for asthma alone, ask your doctor about testing for overlap.

Vinaypriy Wane

Man, I’ve seen too many people in India just grab an asthma inhaler and call it a day-then wonder why they’re gasping at 45. This post? Absolute gold. COPD isn’t just ‘bad asthma’-it’s your lungs screaming for mercy after decades of ignoring them. If you smoke and wheeze, get spirometry. Now.

Diana Campos Ortiz

i’ve had asthma since i was 8 and honestly this is the first time i’ve ever read someone explain the difference without sounding like a textbook. thank you. also, if you’re over 40 and still smoking? please just stop. your lungs aren’t mad, they’re just done.

Jesse Ibarra

Oh wow. Another ‘educational’ post from someone who clearly never had to breathe through a paper bag while their mom yelled at them for using their inhaler too much. Let me guess-you also think COPD is just ‘lazy smokers’? Newsflash: it’s not. And no, your 2018 asthma blog post doesn’t make you a pulmonologist. Stop pretending.

laura Drever

asthma vs copd. yeah sure. i read half of this then got bored. point is: if you cant breathe, see a doc. end of story.

Randall Little

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me that in India, where air pollution is basically a daily inhaler, people are being misdiagnosed with asthma when they actually have COPD? And we wonder why global health outcomes are a mess. This isn’t medicine-it’s a lottery with your lungs.

lucy cooke

Isn’t it poetic? We treat lungs like disposable batteries-use them hard, ignore the warnings, then cry when they die. Asthma is the soul’s protest. COPD is the body’s resignation letter. We don’t need more inhalers-we need more humility.

Trevor Davis

Hey, I just wanted to say thank you for this. My dad’s got COPD, and honestly? We thought it was just bad asthma until last year. He’s been on oxygen for 6 months now. I didn’t know half this stuff. This post literally saved us months of confusion. Also-quit smoking, guys. Seriously. It’s not a character flaw. It’s survival.

John Tran

You know what’s really tragic? That we’ve got this level of medical clarity-spirometry, FeNO, eosinophil counts, CT scans, biologics-and yet, in rural America, in small towns where the clinic closes at 5, people are still being handed albuterol like it’s candy, told to ‘just breathe better,’ and sent home with a pamphlet that says ‘avoid triggers.’ It’s not ignorance. It’s systemic neglect. And it’s killing people in slow motion. The real disease isn’t asthma or COPD-it’s the healthcare system that refuses to see them as separate.

John Pope

Let’s be real: ACOS is the medical equivalent of a hybrid car that doesn’t know if it’s electric or gas. You’re throwing triple therapy at a problem that doesn’t have a textbook solution. We’re treating symptoms, not mechanisms. And we’re calling it ‘personalized medicine’ when it’s really just throwing spaghetti at the wall and hoping one strand sticks. The pharmaceutical industry loves ACOS-it’s a profit engine disguised as a diagnosis.

Clay .Haeber

Ohhh so now we’re diagnosing people based on ‘eosinophil counts’ and ‘FeNO levels’? Next thing you know, we’ll be using astrology to determine bronchodilator dosage. I mean, come on. Back in my day, if you couldn’t breathe, you smoked less and stopped whining. Now we’ve got PhDs writing essays about why your lungs are sad. It’s exhausting.

Adam Vella

It is imperative to underscore that the differential diagnosis between asthma and COPD necessitates a rigorous application of pulmonary function testing protocols, as delineated by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines. Misclassification rates remain unacceptably high in primary care settings due to insufficient training and underutilization of spirometry. Furthermore, the presence of fixed airflow obstruction, as quantified by post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7, remains the gold standard for COPD confirmation. Biologics are not indicated in COPD, as the underlying pathophysiology is not Th2-mediated. This is not a matter of opinion-it is evidence-based medicine.

Pankaj Singh

So you’re telling me that people in India who’ve been breathing smog since birth are being misdiagnosed as asthmatics? No shit. We don’t have spirometers in half the villages. They give them inhalers and send them on their way. Then they die at 52 and the family blames God. This post is useless unless it’s in Hindi and handed out at bus stops.

Robin Williams

just breathe man. it’s not that complicated. your lungs don’t need a PhD to know they’re tired. quit smoking. walk more. stop stressing. your body’s smarter than your google search. i’ve been wheezing since i was 12 and i still run marathons. it’s not the label-it’s the life you live with it.

Kimberly Mitchell

Biologics for asthma? That’s just another way for Big Pharma to charge $100,000 a year for a drug that makes people feel better for six months. And now we’re supposed to believe that eosinophils are the enemy? This isn’t science-it’s a marketing campaign wrapped in jargon. Stop over-medicalizing breathing. Just quit smoking and get some fresh air.