When someone has been on opioids for months or years, and their pain gets worse instead of better, it’s easy to assume they’ve built up a tolerance. But what if the problem isn’t that the drug isn’t working anymore - but that it’s actually making the pain worse? That’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), and it’s being missed far too often in clinics. It’s not rare. It’s not theoretical. It’s happening right now to people who were told their pain was just getting worse. And the fix isn’t more pills - it’s less.

What Opioid Hyperalgesia Really Looks Like

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is a paradox. You take opioids to reduce pain, but over time, your nervous system becomes more sensitive to it. Patients report their original pain - say, lower back pain - doesn’t improve, but now they feel burning in their feet, or even a light touch on their arm feels like a stab. That’s allodynia. That’s not disease progression. That’s the opioids changing how pain signals are processed in the spinal cord and brain. Unlike tolerance, where the body just needs more drug to get the same effect, OIH makes the pain system itself more excitable. Preclinical studies show this involves NMDA receptors, glial cells, and dynorphin release - but you don’t need to understand the biology to spot it in practice. You just need to pay attention to what the patient is telling you.Tolerance vs. Hyperalgesia: The 4 Key Differences

Doctors often treat OIH as tolerance because the symptoms look similar at first glance: dose increases, worsening pain. But the patterns are different.- Response to higher doses: In tolerance, increasing the dose usually brings pain back under control. In OIH, higher doses make pain worse - sometimes dramatically. A patient on 80 mg of oxycodone who says, “It used to help, now I hurt more than ever,” is likely not just tolerant - they’re hyperalgesic.

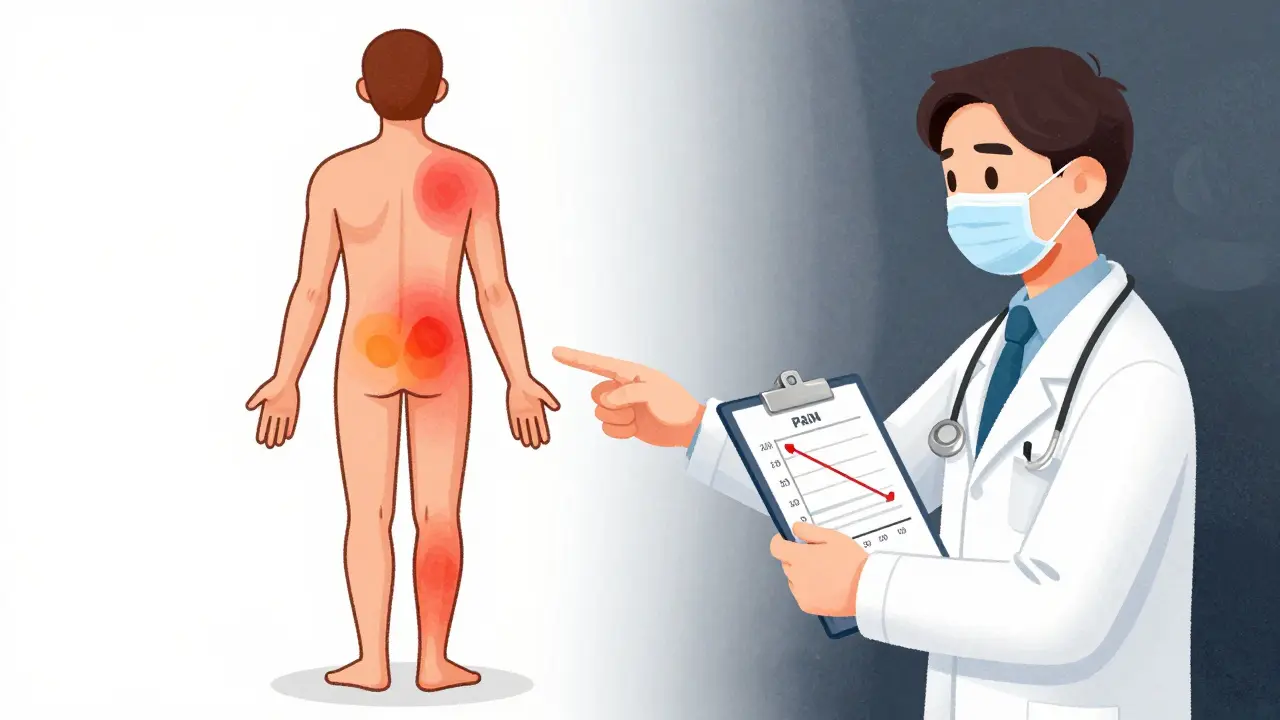

- Pain spread: Tolerance keeps pain in the same place. OIH often spreads. A patient with knee osteoarthritis starts feeling pain in their hip, thigh, and even the opposite knee. Pain drawings show new areas showing up on the body map. That’s a red flag.

- Pain quality: Original pain might be dull and aching. With OIH, it can become sharp, burning, electric, or sensitive to light pressure. Allodynia - pain from something that shouldn’t hurt - is a hallmark.

- Timing: Tolerance builds slowly over weeks. OIH can emerge after months of steady dosing, often without any dose change. The pain gets worse even when the opioid dose hasn’t changed in months.

Why This Gets Missed - And Why It Matters

Most clinicians aren’t trained to look for OIH. Medical schools teach tolerance. They don’t teach paradoxical pain sensitization. So when a patient says, “I need more,” the reflex is to increase the dose. That’s the exact wrong move for OIH. In New Zealand, opioid prescribing dropped 17% between 2018 and 2021 - not just because of addiction concerns, but because doctors started seeing more cases where higher doses made things worse. Medsafe, the country’s medicines regulator, issued a clear warning in 2021: opioids are not recommended for chronic non-cancer pain because of risks like OIH. That’s not opinion. That’s evidence. The Stanford trial NCT00246532, though no longer recruiting, was one of the first to test this systematically. It found that pain sensitivity increased with opioid exposure - even when withdrawal symptoms were ruled out. That’s critical. It means the pain isn’t coming from withdrawal. It’s coming from the drug itself.

How to Diagnose OIH in Practice

You don’t need fancy labs. You need good history and consistent tracking.- Track pain location: Use a body diagram at every visit. Mark where the pain is. If new areas appear over time, especially outside the original injury zone, suspect OIH.

- Record dose-pain relationship: Don’t just note the dose. Ask: “When you increased your dose last month, did your pain get better, stay the same, or get worse?” Write it down. If pain worsens with dose increases, that’s not tolerance - that’s hyperalgesia.

- Test for allodynia: Lightly stroke the skin near the pain site with a cotton swab. If the patient says it hurts, that’s a sign. This isn’t a research tool - it’s a quick clinical check you can do in five minutes.

- Check for other symptoms: OIH often comes with sleep disruption, anxiety, and mood changes that don’t improve with higher opioids. These aren’t side effects - they’re signs the nervous system is stuck in overdrive.

What to Do When You Suspect OIH

Stop increasing the dose. That’s step one. Step two: consider opioid rotation. Switching from morphine to methadone or buprenorphine can help because these drugs have different effects on NMDA receptors. Buprenorphine, in particular, has partial NMDA-blocking properties and may actually reduce hyperalgesia. Step three: consider adding low-dose ketamine or gabapentin. Ketamine, even in tiny amounts, can block NMDA receptors and reset pain sensitivity. Gabapentin works on the same pathways involved in OIH. Neither is a magic bullet, but they can break the cycle. Step four: taper slowly. Don’t stop abruptly. A 10-20% reduction every 2-4 weeks, paired with non-opioid therapies like physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or tai chi, often leads to real improvement. Patients report less pain, better sleep, and more function - even after reducing opioids.

What Doesn’t Work

Adding more opioids. Prescribing antidepressants without addressing the root cause. Blaming the patient for “not coping.” Assuming the pain is psychological because it doesn’t fit a clear anatomical pattern. These are dead ends. OIH isn’t a mental health issue. It’s a neurobiological one. The pain is real. The mechanism is real. The solution isn’t more drugs - it’s a smarter approach.The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about one patient. It’s about how we’ve been treating chronic pain for decades. We’ve over-relied on opioids because they work well short-term. But for long-term non-cancer pain, the risks now clearly outweigh the benefits. The FDA, EMA, and Medsafe all say the same thing: opioids are not first-line for chronic pain. The shift is happening. Prescribing is down. Pain clinics are adopting multimodal approaches. And more doctors are learning to spot OIH before it’s too late. If you’re managing chronic pain with opioids, ask yourself: Is the pain getting better - or just more complicated?Can opioid hyperalgesia happen after just a few weeks of use?

Yes. While OIH is more common after months of use, studies have shown it can develop in as little as 2-4 weeks, especially with high doses or potent opioids like fentanyl or hydromorphone. It’s not just a long-term problem.

Is opioid hyperalgesia the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, craving, and loss of control. OIH is a physiological change in pain processing - you can have it without being addicted. Many patients on long-term opioids for chronic pain develop OIH but don’t misuse their medication.

Can you test for opioid hyperalgesia with a blood test or scan?

No. There’s no blood test, MRI, or X-ray that confirms OIH. Diagnosis is clinical - based on symptoms, pain mapping, dose-response patterns, and ruling out other causes. Quantitative sensory testing can help in research settings, but in clinics, it’s about listening and tracking changes over time.

If I reduce my opioid dose, will my pain get worse at first?

It might. That’s not OIH worsening - that’s withdrawal or the nervous system readjusting. But unlike with tolerance, where pain returns to baseline after a dose increase, with OIH, pain often improves over weeks after a slow taper. Many patients report their original pain actually gets better once the opioid-induced sensitization fades.

Are there alternatives to opioids for chronic pain that avoid OIH?

Yes. Non-opioid options like physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, tai chi, NSAIDs, gabapentin, and even low-dose naltrexone have strong evidence for chronic pain. Multimodal programs that combine several approaches are more effective and safer than long-term opioids. Many patients find they feel better overall - not just less pain - when they move away from opioids.

christy lianto

My dad was on opioids for 5 years after a back surgery. They kept upping his dose until he couldn’t walk without crying. Then we found a pain specialist who said, ‘You’re not tolerant-you’re hyperalgesic.’ We tapered him slow. Six months later, he’s gardening again. No pills. Just movement and sleep. This isn’t theory-it’s life-changing.

Luke Crump

Oh wow, so now we’re blaming the drug instead of the patient’s weak constitution? Next they’ll say caffeine causes insomnia and gravity is just a suggestion. If your pain gets worse with opioids, maybe you’re just addicted and refusing to admit it. Stop looking for excuses and take responsibility.

Annette Robinson

I’m so glad someone’s talking about this. I’ve seen too many patients get trapped in this cycle. It’s heartbreaking. The system rewards prescribing more, not thinking deeper. But when you actually listen-when you map the pain, check for allodynia, track the pattern-it becomes undeniable. OIH isn’t a myth. It’s a failure of education.

Ken Porter

This is why America’s healthcare is broken. We over-medicalize everything. Just tell people to toughen up. Opioids work. If they don’t, they’re weak. Stop making up fancy terms to justify giving up.

swati Thounaojam

i read this in india and its so true. here too doctors just give more pills. no one listens. pain is real but no one sees it.

Donny Airlangga

My sister had OIH. She was on 120mg oxycodone daily. When they finally tapered her, she cried for weeks-not from withdrawal, but because she realized she’d been in agony for years and thought it was normal. That’s the tragedy. Not the addiction. The silence.

Molly Silvernale

It’s like… the body screams, ‘I’m not broken-I’m being poisoned!’ and the system replies, ‘Here, take more poison. It’ll fix the scream.’ We’ve turned healing into a feedback loop of violence disguised as care. Opioid hyperalgesia isn’t a diagnosis-it’s a confession. The medicine is the problem.

Evan Smith

So… if I take more and it hurts more, I’m not addicted? I’m just… extra sensitive? Like my nerves are on TikTok? Lol. But seriously-this makes sense. My cousin’s pain got worse after the last dose bump. Now he’s off them. Feels like a new person.

Lois Li

Thank you for writing this. I work in a rural clinic and we don’t have specialists. But I started doing the cotton swab test last year. One patient said, ‘I didn’t know it was supposed to hurt to brush my arm.’ That moment changed everything. We’re not just treating pain-we’re listening to the body’s language.

Manish Kumar

Let me think about this for a moment. The nervous system is a delicate instrument, yes? Like a violin string that, when over-tuned, begins to vibrate at frequencies it was never meant to. Opioids, in their noble attempt to silence the cry of pain, instead turn the entire body into a resonating chamber of suffering. We mistake the echo for the source. We give more of the instrument to silence the noise-but the noise is the instrument itself, screaming. The solution? Not louder music. Not more strings. But tuning. Careful. Patient. Reverent tuning.

Aubrey Mallory

Stop gaslighting patients who’ve been mismanaged for years. This isn’t ‘alternative medicine.’ This is basic neurology. If your pain spreads, if light touch hurts, if more drugs make it worse-you’re not ‘drug-seeking.’ You’re being failed by a system that treats numbers more than humans. I’ve seen this. I’ve fought for it. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s not real.

Dave Old-Wolf

I was told I was tolerant. Took 3x my dose. Pain got worse. Then I met a physiatrist who asked, ‘When was the last time you felt normal?’ I couldn’t remember. We tapered. Took 6 months. Now I hike. I sleep. I laugh. OIH is real. And it’s survivable.

Prakash Sharma

Why are we listening to American doctors? In India, we know pain is part of life. You work through it. You don’t whine and blame medicine. This OIH thing is just another Western weakness. Take the pills. Be strong.

Kristina Felixita

I’m a nurse. I’ve watched patients cry because they were told their pain was ‘all in their head.’ Then we found OIH. We tapered. They started painting again. One man drew his pain map-red everywhere-and then, months later, drew just one small spot. He said, ‘I didn’t know I could feel like this again.’ This isn’t science. It’s grace.