Drug Clearance Calculator

Enter Medication Details

Drug Characteristics

High-extraction drugs (e.g., Fentanyl, Morphine):

Rely on liver blood flow - significant dose reduction needed

Low-extraction drugs (e.g., Metformin, Diazepam):

Rely on enzyme function - moderate dose reduction

Dose Adjustment Result

Adjusted Dose:

This is based on:

- Liver disease severity:

- Drug extraction ratio:

When your liver is damaged, it doesn’t just affect how you feel-it changes how your body handles every pill you take. For people with liver disease, common medications can become dangerous if dosed the same way as for someone with healthy liver function. The problem isn’t always obvious. You might take a standard dose of a painkiller or sedative and end up with confusion, drowsiness, or even coma-not because you’re overdosing on purpose, but because your liver can’t clear the drug like it used to.

Why the Liver Matters for Drug Clearance

The liver is your body’s main drug-processing plant. It breaks down most medications so they can be eliminated through urine or bile. This process relies on enzymes like CYP3A4 and CYP2E1, which are responsible for oxidizing drugs into forms your body can get rid of. In liver disease, these enzymes don’t work as well. Studies show CYP3A4 activity drops by 30-50% in cirrhosis, and CYP2E1 can fall by as much as 60%. That means drugs stay in your system longer, building up to toxic levels even at normal doses.It’s not just enzymes. The liver also uses transport proteins like OATP1B1 to pull drugs into liver cells for processing. In advanced liver disease, these transporters are reduced by 50-70%. So even if the enzymes are still somewhat active, the drugs can’t even get inside the liver to be broken down.

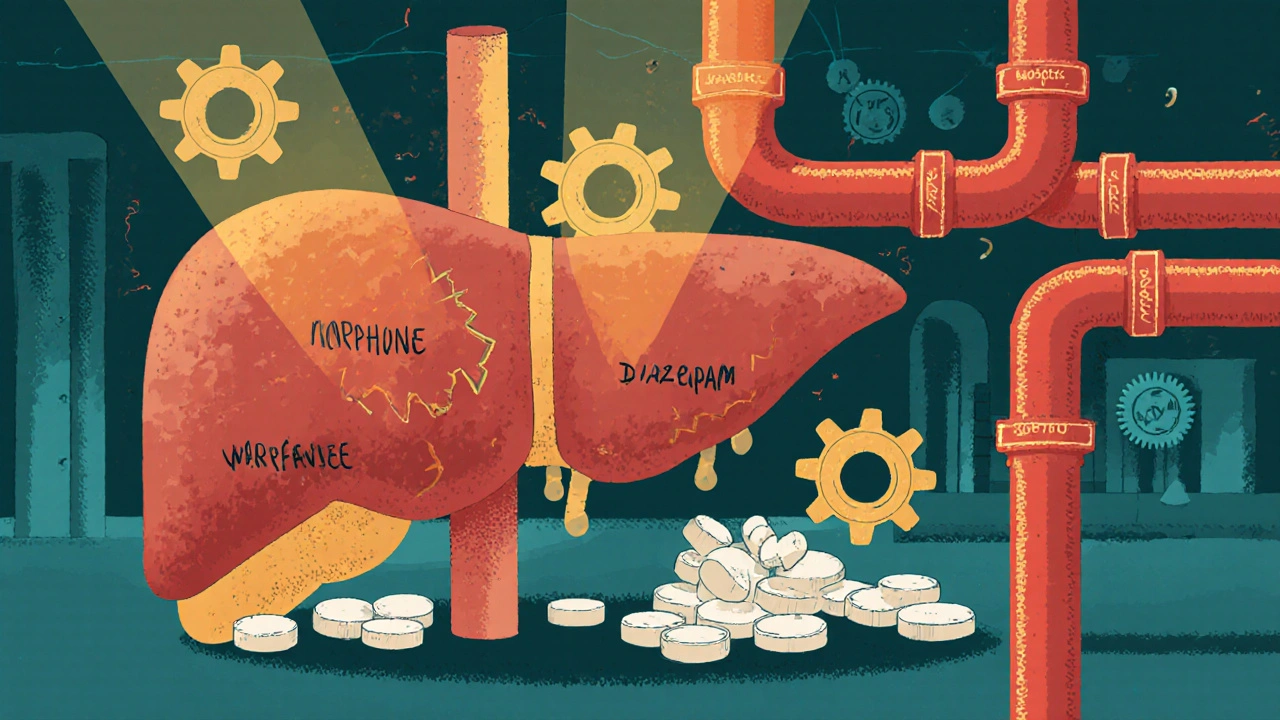

Then there’s blood flow. A healthy liver gets about 1.5 liters of blood per minute. In cirrhosis, that drops to 0.8-1.0 liters. Worse, up to 40% of that blood bypasses the liver entirely through abnormal connections called portosystemic shunts. This means drugs taken by mouth-like opioids or benzodiazepines-skip the first-pass metabolism and flood directly into your bloodstream. The result? Higher drug levels than expected, faster.

High-Extraction vs. Low-Extraction Drugs: What’s the Difference?

Not all drugs are affected the same way. They’re grouped by their extraction ratio-how much of the drug the liver removes in one pass.- High-extraction drugs (ratio >0.7): These are cleared mostly by blood flow. Examples: fentanyl, morphine, propranolol. If blood flow drops, clearance drops with it. Dose reductions of 50-75% are often needed in severe liver disease.

- Low-extraction drugs (ratio <0.3): These are cleared by enzyme activity, not blood flow. Examples: diazepam, lorazepam, methadone, warfarin. Since enzyme function is impaired, these drugs build up slowly but steadily. About 70% of commonly prescribed drugs fall into this category, making them the biggest hidden risk.

Here’s the catch: even if a drug is low-extraction, it doesn’t mean it’s safe. Warfarin, for example, is metabolized almost entirely by the liver. In cirrhosis, its clearance drops by 30-50%. That’s why INR levels can spike unpredictably-leading to dangerous bleeding-even when the dose hasn’t changed.

Real-World Risks: Which Drugs Are Most Dangerous?

Some medications are far more likely to cause harm in liver disease. The FDA and EASL have flagged several based on clinical evidence:- Benzodiazepines: Diazepam has active metabolites that stick around for days. In cirrhosis, dose reductions of 50-70% are needed. Lorazepam, which doesn’t form active metabolites, only needs a 25-40% reduction.

- Opioids: Morphine and codeine are risky because they can trigger hepatic encephalopathy. Even small doses can cause confusion or coma. Fentanyl is slightly safer due to its short half-life, but still requires 50% dose reduction in Child-Pugh B/C.

- Antibiotics: Ceftriaxone, often used in liver disease patients with infections, can reach 40-60% higher blood levels due to reduced clearance. That increases the risk of side effects like diarrhea or allergic reactions.

- Antivirals: Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C need careful dosing. The TARGET-HepC study found that 22.7% of patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis had treatment failure when given standard doses-compared to just 5.3% when doses were adjusted.

On the flip side, some drugs are mostly safe. Sugammadex, used to reverse muscle relaxants during surgery, is 96% cleared by the kidneys. No dose adjustment is needed-even in severe liver disease. But even here, recovery time was 40% longer in transplant patients, showing that liver disease still affects how the body responds.

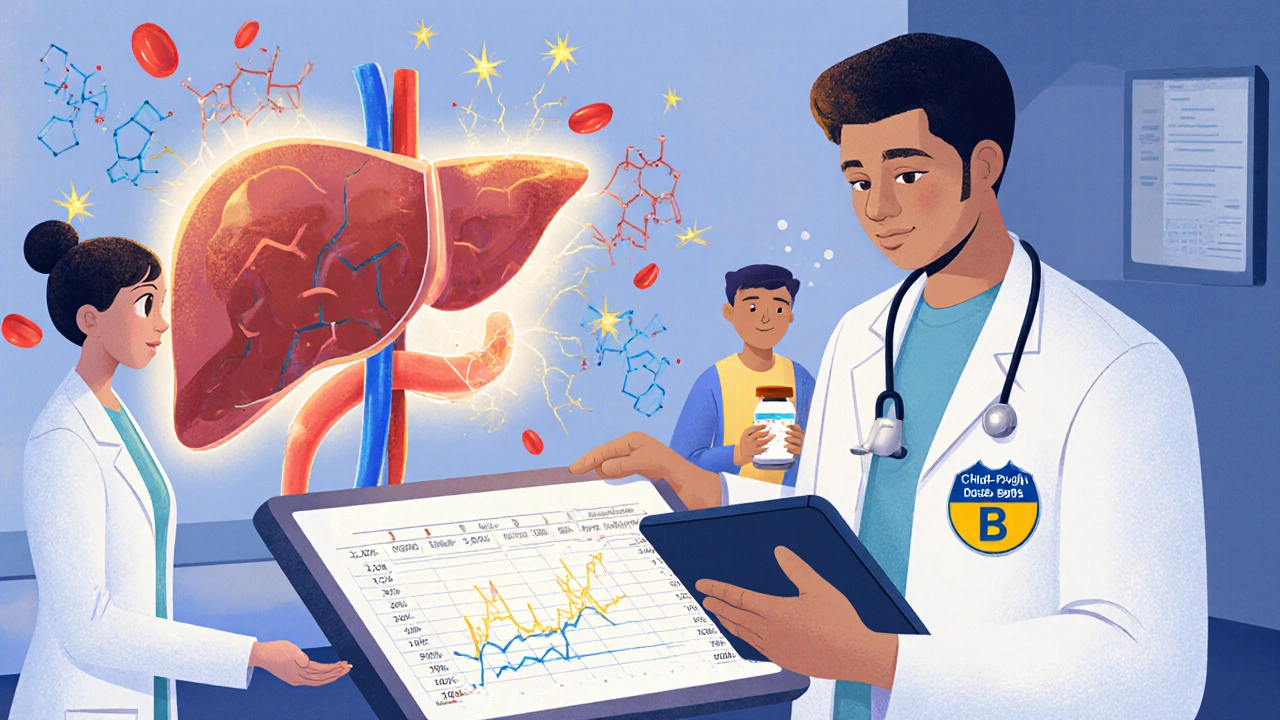

How Doctors Measure Liver Function-And Why It Matters

You can’t rely on a single blood test to know how well your liver is working. ALT and AST levels don’t tell you about drug metabolism capacity. Instead, doctors use two systems:- Child-Pugh Score: Based on bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, and encephalopathy. Class A (mild), B (moderate), C (severe). Dose reductions are recommended based on class: 25-50% for B, 50-75% for C.

- MELD Score: Uses bilirubin, INR, and creatinine. For every 5-point increase above 10, drug clearance drops by about 15%. It’s especially useful for predicting outcomes in advanced disease.

But even these scores aren’t perfect. A 2023 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics showed that drug levels don’t reliably correlate with liver test results. Two patients with the same MELD score might metabolize a drug completely differently. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is critical for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, phenytoin, or lithium.

What’s Changing in Drug Development and Dosing

The pharmaceutical industry is finally catching up. In 2023, the FDA approved 18 new drugs with specific dosing instructions for liver impairment-a 25% jump from 2022. By 2024, 92% of new drug applications included dedicated liver impairment studies, up from 65% in 2018.Now, researchers are using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to predict how drugs behave in diseased livers. These models account for reduced blood flow, fewer liver cells, and shunting. They’re accurate 85-90% of the time. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance encourages using this tech to set smarter doses from day one.

Dr. Aleksandra Galetin from the University of Manchester predicts that within five years, 70% of new drug labels will include model-based dosing recommendations-not just vague warnings like “use with caution.”

What Patients and Providers Should Do Now

If you or someone you care for has liver disease, here’s what matters:- Always tell your doctor and pharmacist about your liver condition-even if you think it’s “mild.”

- Ask: “Is this drug cleared by the liver? Do I need a lower dose?”

- For high-risk drugs like opioids, benzodiazepines, or anticoagulants, request therapeutic drug monitoring.

- Don’t assume “natural” or “over-the-counter” is safe. Herbal supplements like kava, comfrey, or high-dose vitamin A can be toxic to a damaged liver.

- Watch for signs of drug toxicity: confusion, extreme drowsiness, unsteady walking, nausea, or unusual bruising.

Pharmacists are stepping up, too. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists reports a 40% increase in pharmacist-led dose adjustment services for liver disease patients between 2020 and 2023. These services aren’t just helpful-they’re life-saving.

The Bigger Picture: Fatty Liver Isn’t Just “Mild” Anymore

Many people assume that if they don’t have cirrhosis, their liver is fine. But metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly called NAFLD, affects 30% of U.S. adults. Even in early stages, before scarring, CYP3A4 activity drops by 15-25%. That means common drugs like statins, antidepressants, or even some pain relievers might not be cleared properly.And here’s the hard truth: patients with advanced liver disease don’t get more drug reactions than others-but they tolerate them far worse. Their organs are already stretched thin. A side effect that’s just annoying in a healthy person can be catastrophic here.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. But the future is moving toward personalized dosing-combining liver function scores, genetic testing (like CYP2C9*3 status), and PBPK models. For now, the best protection is awareness. Your liver doesn’t just heal your body. It keeps your medications working safely. When it’s damaged, every pill becomes a calculation.

Can I still take painkillers if I have liver disease?

Yes, but carefully. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is generally safe at doses up to 2,000 mg per day in mild to moderate liver disease. Avoid higher doses and never combine it with alcohol. NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen can worsen kidney function and increase bleeding risk, especially with low platelets or ascites. Opioids like codeine or oxycodone should be avoided or used at 50% reduced doses with close monitoring for drowsiness or confusion.

Why do some drugs need lower doses while others don’t?

It depends on how the drug leaves your body. If it’s cleared mostly by the kidneys (like sugammadex or most antibiotics), liver disease won’t affect it much. But if the liver breaks it down (like warfarin, diazepam, or morphine), reduced enzyme activity and blood flow mean the drug stays in your system longer. Drugs with a wide safety margin (like some antihistamines) may not need adjustment. But those with a narrow window-where too little doesn’t work and too much is toxic-require careful dose changes.

Does alcohol use make liver-related drug problems worse?

Absolutely. Alcohol directly damages liver cells and reduces enzyme activity. Even if you’ve stopped drinking, long-term alcohol use can leave lasting changes in how your liver processes drugs. If you have a history of alcohol-related liver disease, assume your drug clearance is reduced-even if your blood tests look okay. Avoid alcohol completely while taking any medication.

Can liver function improve enough to go back to normal drug doses?

In some cases, yes. If liver disease is caught early and the cause is treated-like stopping alcohol, losing weight for MASLD, or curing hepatitis C-liver function can improve. Enzyme activity and blood flow may partially recover. But this doesn’t happen overnight. Dose adjustments should be reviewed every 3-6 months with your doctor. Never assume you can return to a previous dose without testing and medical approval.

Are herbal supplements safe for people with liver disease?

No, many are not. Supplements like kava, green tea extract, comfrey, and high-dose vitamin A have been linked to liver injury-even in people without prior disease. In those with existing liver damage, they can cause rapid worsening. There’s no regulation to guarantee safety or purity. Always tell your doctor about every supplement you take. When in doubt, avoid them.

What’s the role of therapeutic drug monitoring in liver disease?

It’s essential for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, or certain antibiotics. Blood tests measure actual drug levels so your doctor can adjust the dose based on what’s in your body, not just what’s on the label. This reduces the risk of toxicity and improves outcomes. If you’re on one of these drugs and have liver disease, ask if TDM is right for you.

Monika Wasylewska

Been there. My mom had cirrhosis and they gave her a standard dose of diazepam for anxiety. She was out cold for 36 hours. No one warned us. The docs just assumed liver = fine. We learned the hard way.

Always ask: 'Is this safe for my liver?'

Jackie Burton

Let’s be real - Big Pharma doesn’t care. They push the same dosing guidelines because it’s profitable. They know 30% of patients have undiagnosed fatty liver. They profit off the toxicity. The FDA? Complicit. CYP enzymes? Just a footnote in the appendix. Wake up.

They’re poisoning us slowly and calling it 'standard care'.

Philip Crider

Bro. I had a buddy with alcoholic cirrhosis take OxyContin at 10mg tid. He ended up in the ICU. Not because he was a junkie - because his liver was a ghost town. Blood flow? Gone. Enzymes? Out to lunch.

Meanwhile, the docs are still prescribing like we all have perfect livers. 🤦♂️

It’s not just meds - it’s everything. Even that 'natural' turmeric supplement? Liver murder. 🤕

Diana Sabillon

This is so important. I work in hospice and see this all the time. Families are terrified their loved one is overdosing - but it’s just the liver failing. No one explains it in plain terms. Thank you for writing this. It’s a lifeline.

People need to know: it’s not their fault. It’s the system.

neville grimshaw

Oh, sweet merciful god, another dry medical essay. I came here for drama, not a pharmacology lecture.

Can we at least get a meme? A liver with a 'Do Not Enter' sign? I’d share that on my feed. 🤡

Also, who wrote this? PhD? Because if so, congrats - you’ve mastered the art of making liver disease sound like a TED Talk on tax law.

Carl Gallagher

It’s fascinating how little most clinicians understand about hepatic drug kinetics. The extraction ratio concept is critical - high-extraction drugs like morphine are far more sensitive to reduced hepatic blood flow than low-extraction ones like ibuprofen. But here’s the kicker: even low-extraction drugs can become problematic in advanced disease because of transporter downregulation and altered protein binding.

And let’s not forget the gut-liver axis. Portal hypertension alters intestinal permeability, which changes oral bioavailability. Most guidelines ignore this. We’re treating patients like they’re textbook models, not complex, broken systems.

bert wallace

My uncle’s a retired hepatologist. He says the same thing: 'If you don’t know the patient’s Child-Pugh score, don’t prescribe.' Simple. But no one checks. They just copy-paste the script.

And don’t even get me started on NSAIDs. People think 'over-the-counter' means 'safe.' Nope. Liver’s already tired. Don’t make it carry the groceries too.

Neal Shaw

Correct. The reduction in CYP3A4 activity in cirrhosis is well-documented in Hepatology (2021;74:1123-1135). Clearance of midazolam, for example, is reduced by 60-70% in Child-Pugh C patients. Dosing adjustments should be based on functional reserve, not just serum bilirubin.

Also, avoid drugs with narrow therapeutic indices - warfarin, digoxin, theophylline. Use alternatives like acetaminophen (≤2g/day) or non-pharmacological options where possible.

Hamza Asghar

Of course you’re talking about CYP enzymes - because you’re one of those 'I read a textbook once' types. Real doctors don’t memorize ratios. They look at the patient. You think your 'extraction ratio' magic formula saves lives? Nah. It just makes you feel smart.

Meanwhile, the guy with alcoholic hepatitis is still getting 10mg of oxycodone because his chart says '55 y/o male, no allergies.'

Pathetic.

Karla Luis

So basically, if you have liver issues, every pill you take is a Russian roulette spin

And the doctors? They’re just shrugging like it’s normal

Also, why is everyone still prescribing benzos to cirrhotics?? 😒

Someone please tell me this isn’t still happening

jon sanctus

It’s all about control. The system wants you dependent. Why? Because if you’re sick, you keep buying meds. Liver failure? Just add another drug to 'manage the side effects.'

It’s not medicine. It’s a pyramid scheme with white coats.

And don’t get me started on the 'liver cleanse' scams - those are the real killers.

Kenneth Narvaez

High-extraction drugs are flow-dependent. Low-extraction are capacity-dependent. In cirrhosis, both are compromised. Clearance = Qh * ER + (1-ER) * CLint. ER drops due to shunting. CLint drops due to enzyme loss. Therefore, AUC increases disproportionately. No algorithm replaces clinical judgment. But you already knew that.

Christian Mutti

My heart goes out to every patient who has been failed by this broken system. 🥺

Every time a loved one slips into hepatic encephalopathy because a doctor didn’t adjust a dose - it’s a tragedy. A moral failure. We must demand better. We must raise our voices. 🙏

And yes - I cried reading this. It’s beautiful. And heartbreaking.

Liliana Lawrence

Thank you SO MUCH for sharing this!! 💖💖💖

My cousin was misdiagnosed for YEARS because everyone thought her fatigue was 'just stress' - turns out she had stage 3 cirrhosis and was on a standard dose of gabapentin for 'anxiety'...

She almost died. Now she’s on a liver specialist’s regimen. But why did it take so long??

WE NEED MORE EDUCATION!! 🙏🙏🙏

Sharmita Datta

Have you considered that this is all a distraction? The real cause of liver damage is glyphosate in the food supply. The pharmaceutical industry uses liver disease as an excuse to sell more drugs. The CYP enzyme theory? A myth created by Big Pharma to justify profit-driven dosing. The WHO is complicit. I’ve seen the documents.

mona gabriel

My dad’s been sober 12 years. His liver’s still messed up. He takes one Tylenol a day for his knee and I still panic. You don’t know what’s 'safe' until you’ve watched someone slip into hepatic coma.

It’s not just meds. It’s the silence around it. We don’t talk about this enough.

Phillip Gerringer

People with liver disease are lazy. They drink. They eat junk. They don’t care. Now they want the system to bend for them? No. If you destroyed your organ, you don’t get a free pass on dosing. Take responsibility. Stop blaming doctors.

And stop taking opioids. You’re just addicted. Don’t hide behind 'liver disease'.

jeff melvin

Acetaminophen is the only safe OTC analgesic in liver disease - under 2g/day. NSAIDs? Avoid. Benzodiazepines? Avoid. Opioids? Use lowest effective dose with extreme caution. CYP3A4 substrates? Monitor. That’s it. No need for essays. Just follow the guidelines.

Matt Webster

Thank you for writing this. I’ve seen too many patients get lost in the system. This isn’t just about pharmacology - it’s about compassion. If you’re reading this and you’re a clinician: pause. Ask. Adjust. Listen. You might save someone’s life - not just their liver.