Warfarin Dosing Calculator

Your Information

Genetic Markers

Recommended Warfarin Dose

Note: This calculator estimates dose based on CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetics as described in the article. Actual dosing should be determined by a healthcare professional.

Important: This dose recommendation includes a 20-30% safety margin to reduce bleeding risk.

When you take a pill, your body doesn’t treat it the same way everyone else does. Two people with the same diagnosis, same dose, same doctor - one gets relief, the other gets sick. Why? It’s not about willpower, adherence, or luck. It’s often about genetics - and the ethnic background that loosely reflects those genetic patterns.

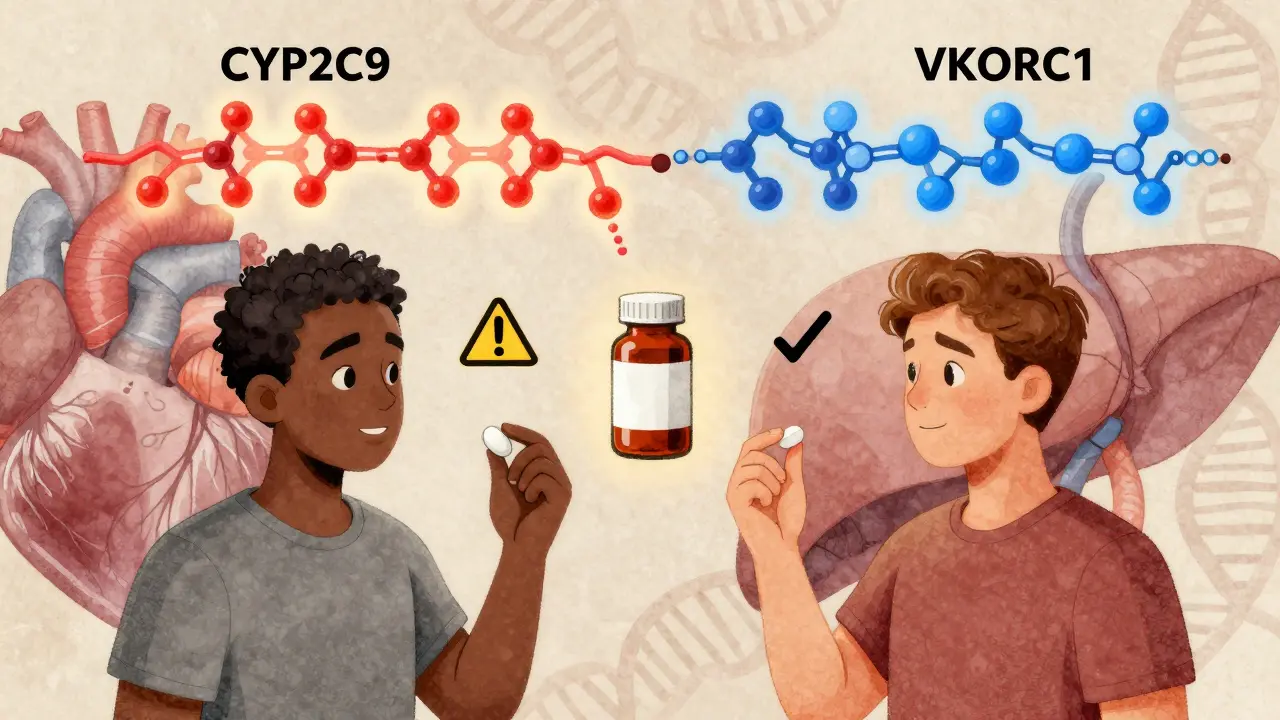

Why Some Drugs Work Better for Some People

Take warfarin, a blood thinner used after heart attacks or for atrial fibrillation. European Americans typically need about 20% less than African Americans to reach the right blood-thinning level. Why? Because of differences in two genes: CYP2C9 and VKORC1. These genes control how fast your body breaks down the drug. In African Americans, certain variants of CYP2C9 are common - variants that aren’t found in most Europeans. That means the drug sticks around longer, so a lower dose prevents dangerous bleeding. But if you just guess the dose based on weight or age, you’re playing Russian roulette with side effects. This isn’t rare. Around 20% of drugs approved by the FDA between 2000 and 2010 showed clear differences in how well they worked - or how dangerous they were - across ethnic groups. Some people get no benefit. Others get severe rashes, liver damage, or even death from doses that are perfectly safe for others.The Real Culprits: Genes, Not Race

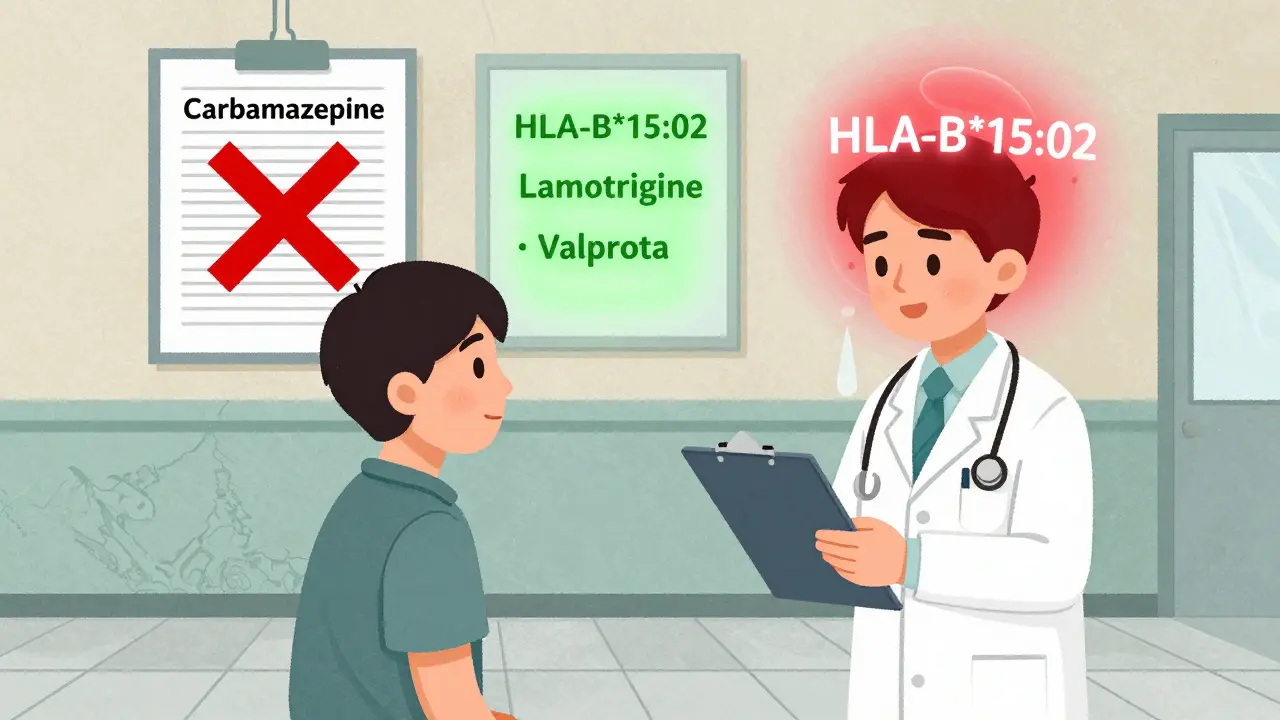

Race is a social category. It doesn’t exist in your DNA. But your genes? They’re real. And they’re shaped by where your ancestors lived - whether that was West Africa, East Asia, Scandinavia, or the Andes. One of the clearest examples is carbamazepine, a drug for epilepsy and nerve pain. In Han Chinese, Thai, and Malaysian populations, about 1 in 10 people carry a gene variant called HLA-B*15:02. If they take carbamazepine, they have a 1,000 times higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome - a life-threatening skin reaction. In Europeans, Africans, and Japanese, that variant is almost nonexistent. So in countries like Taiwan and Thailand, doctors test for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine. In the U.S., they often don’t - even though Asian patients are regularly prescribed it. The same goes for clopidogrel (Plavix), used after stents or heart attacks. About 1 in 5 East Asians carry a gene variant that makes the drug useless. Their bodies can’t activate it. They’re left with a clotting risk they don’t even know about - because their doctor assumed the drug would work.Blood Pressure Drugs and the African American Paradox

African Americans are more likely to have high blood pressure. But they respond poorly to two of the most common classes of blood pressure drugs: ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Studies show they get 30-50% less benefit than European Americans. So in 2005, the FDA approved a combo drug - isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine - specifically for self-identified African American patients with heart failure. It was the first drug approved for a racial group. The results? In clinical trials, it cut mortality by 43%. Sounds great. But here’s the catch: 35% of African American patients still didn’t respond. And many European Americans actually responded better than average. So why use race at all? Because genetics are messy. The same gene variants that affect drug response in African Americans are also found in some Europeans and Latinos - just less often. Race is a shortcut. A rough filter. Not a rule.The Asthma Puzzle: Why Albuterol Fails for Some

Asthma drugs like albuterol (Ventolin) work by relaxing airways. But in people with African ancestry, the drug often doesn’t work as well. Why? A gene called ADRB2 has a variant called Gly16Arg. It’s found in 50-60% of African populations, 40-50% of Asians, but only 25-30% of Europeans. This variant makes the receptor in the lungs shut down faster after albuterol use - so the drug wears off quicker. In one study, patients with African ancestry had 33% less bronchodilation than those with European ancestry - even when given the same dose. If you’re Black and your inhaler isn’t helping, it’s not because you’re not using it right. It’s because your genes changed how your body responds.

What About G6PD Deficiency?

If you have ancestry from malaria-prone regions - Sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean, Southeast Asia - you might carry G6PD deficiency. It’s a genetic quirk that protects against malaria. But it makes you vulnerable to certain drugs: primaquine (for malaria), dapsone (for leprosy), and some sulfa antibiotics. These drugs can trigger hemolysis - your red blood cells bursting open. That’s dangerous. It can lead to kidney failure or death. In African American males, 10-14% have this deficiency. In parts of Southeast Asia, it’s as high as 30%. Yet, most doctors don’t test for it unless a patient has a history of anemia or jaundice. That’s a gap.The Problem With Using Race as a Proxy

Using race to decide your treatment sounds practical. But it’s flawed. A Nigerian and a Khoisan person from South Africa are both labeled “Black” - but genetically, they’re more different from each other than either is from a German. A Mexican patient might have 80% Indigenous ancestry, 15% European, and 5% African. Which genes matter? The American Heart Association and the NIH now say: stop using race as a stand-in for genetics. Instead, test for the actual variants. The FDA is moving in that direction too. New drug labels now say “test for CYP2C19*2” - not “avoid clopidogrel in Asians.” They’re shifting from ethnicity to exact DNA markers.What’s Being Done About It?

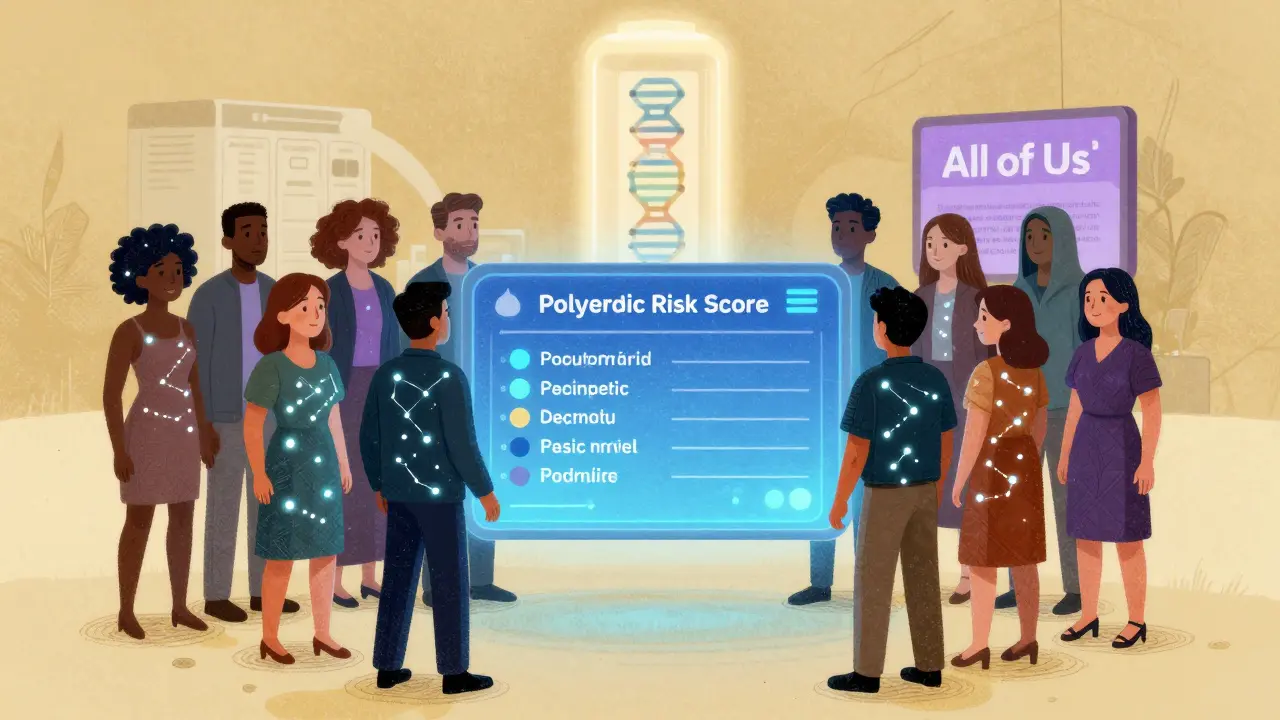

The NIH’s All of Us program is sequencing DNA from 3.5 million Americans - 80% from racial and ethnic minorities. For the first time, we’re building a database that reflects real human diversity, not just European genomes. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have been genotyping patients for years. In their programs, adverse drug events dropped by 28-35%. That’s not magic. It’s precision. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) now has 27 gene-drug guidelines. For example:- If you’re a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer - don’t use clopidogrel. Use prasugrel or ticagrelor instead.

- If you have HLA-B*15:02 - avoid carbamazepine. Use lamotrigine or valproate.

- If you’re a CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer - codeine won’t work. It turns into morphine too fast. Use oxycodone instead.

Rawlson King

This isn't about race. It's about ancestry and genetic variation. Using ethnic labels as proxies is lazy medicine. We've known for decades that CYP enzymes vary by population. The real issue is that we're still using 1950s diagnostic logic in a 2020s genomic world.

Stop grouping people by skin tone and start testing for actual variants. It's not complicated. It's just inconvenient for the system.

Bruno Janssen

I had a cousin who went blind from a reaction to a common antibiotic. They never tested her. She was Mexican. They just assumed she'd be fine. This isn't theoretical. It's personal.

Scott Butler

So now we're going to DNA test every American before giving them aspirin? This is how socialism creeps in. Next they'll be profiling us by haplogroup before letting us buy coffee. Wake up people.

Emma Sbarge

It's not about race. It's about access. The people who need these tests the most can't afford them. The ones who can afford them don't need them. That's the real injustice here.

We're talking about precision medicine, but we're still running a one-size-fits-all insurance model. That doesn't add up.

Deborah Andrich

My grandma took warfarin for 12 years. Every time they changed her dose, she almost bled out. No one ever asked about her roots. She was from Jamaica. Turns out, she had the CYP2C9 variant. If they'd tested her in 2008, she wouldn't have spent half her retirement in the hospital.

We need to stop pretending this is about biology and start treating it like a public health crisis. People are dying because we're too cheap to test.

Constantine Vigderman

OMG this is SO important!! I just found out I'm a CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer and now I get why codeine made me hallucinate 😱

Why isn't this taught in med school?? I'm telling everyone I know to get tested!! 🙌 #Pharmacogenomics #LifeChanging

Cole Newman

Bro you're telling me my uncle died because he was Black and they gave him the wrong dose? That's messed up. My cousin took Plavix and got a stroke. He's half Filipino. They never said anything. This whole system is rigged.

Casey Mellish

As an Australian with mixed Aboriginal and Irish ancestry, I've had three different drug reactions that were never explained. No one ever considered my genetic background beyond 'white'.

It's not about race. It's about the fact that most pharmacogenomic data comes from Northern Europeans. We're all just guessing. And people are paying with their lives.

Tyrone Marshall

Let’s not confuse correlation with causation. Ethnicity is a social construct, but genetic clusters are real. The problem isn't using population data-it's using it as a substitute for testing.

Imagine if we diagnosed diabetes based on whether someone 'looked overweight' instead of checking blood glucose. That’s what we’re doing here.

Testing should be routine, not optional. The science is here. The infrastructure is lagging. That’s the real barrier.

Emily Haworth

Big Pharma doesn't want this. They make billions selling one-size-fits-all pills. They're funding studies that say 'race doesn't matter' because if we start testing, they lose their monopoly on dumb drugs. 🕵️♀️💉

They even lobbied to block HLA-B*15:02 testing in the US. It's not science-it's profit.

Tom Zerkoff

It is imperative to underscore that the current paradigm of pharmacological intervention remains fundamentally flawed in its reliance on population-based heuristics rather than individualized molecular profiling. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines represent a paradigm shift, yet their implementation remains critically underfunded and underutilized across the majority of clinical settings in the United States. The ethical imperative to transition to genotype-guided prescribing is not merely a scientific advancement-it is a moral obligation.

Yatendra S

Genetics is just a new form of colonialism. They test your DNA, then use it to decide if you're 'worthy' of better care. Meanwhile, the rich get personalized medicine and the poor get the same old guesswork.

Why not fix the healthcare system first? Instead of testing genes, fix the waiting lists, fix the cost, fix the racism.

Science without justice is just another tool of oppression.

Himmat Singh

The premise is fundamentally flawed. Genetic variation exists along clines, not discrete ethnic categories. To claim that 'African Americans' respond differently to drugs is to reify a biological fiction. The data is noisy, the sample sizes are small, and the confounding variables are ignored.

What we need is not more genetic testing, but better clinical trials with diverse enrollment and proper statistical controls. This is not precision medicine-it's pseudoscience dressed in lab coats.

kevin moranga

I’ve been on antidepressants for 10 years. Tried 7 different ones. Some made me suicidal. Others did nothing. I finally got tested last year-turns out I’m a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Switched to sertraline and boom-life changed.

Why did it take a decade? Why didn’t my doctor know? Why isn’t this standard? I’m not special. I’m just lucky.

If you’re on meds and they’re not working or you’re having side effects? Ask for the test. It’s not expensive. It’s not magic. It’s just science. And it saved my life.

Webster Bull

Test your genes. Not your race.

Rawlson King

And that’s why the FDA’s new labeling guidelines are a step forward. They don’t say 'avoid in Asians.' They say 'test for CYP2C19*2.' That’s the future.

Stop letting race be the lazy shortcut. We have the tools. We just need the will.