When a pharmacist pulls a prescription off the system, they don’t just see "lisinopril." They see generic lisinopril, authorized generic lisinopril, or a branded generic like Zestril. And that difference? It matters. Not because the medicine works differently-but because the system telling them what to dispense might be wrong, outdated, or missing key details. In today’s pharmacy workflows, correctly identifying whether a drug is brand or generic isn’t just about cost savings. It’s about safety, compliance, and patient trust.

How Pharmacy Systems Tell Generic Apart from Brand

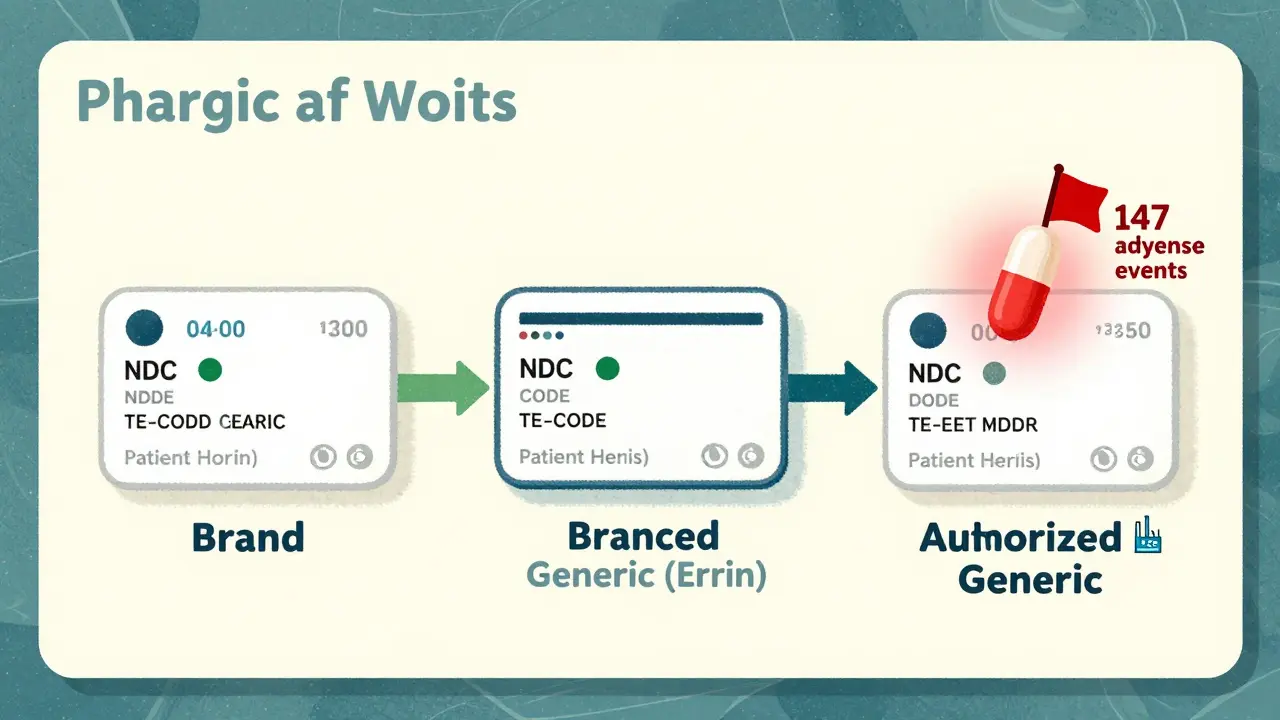

At the heart of every pharmacy system is the National Drug Code (NDC). This 10- or 11-digit number is like a fingerprint for each drug product. A brand-name drug and its generic version each have their own unique NDC. Even if two generics have the same active ingredient, different manufacturers mean different NDCs. Systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 pull this data from the FDA’s Orange Book-the official list of approved drugs with therapeutic equivalence ratings. The Orange Book uses two-letter Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) codes to classify drugs. If a drug has an "AB" code, it means it’s bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That’s the gold standard. But here’s where things get messy: "AO" and "AN" codes? Those are for drugs that aren’t fully tested for equivalence, often because they’re complex-like inhalers or topical creams. And then there are authorized generics. These are made by the original brand company but sold under a generic label. They’re identical in every way, but pharmacy systems often don’t flag them clearly. A pharmacist might see "Lisinopril 10mg" and have no idea it’s the exact same pill as Zestril, just cheaper. Branded generics add another layer. Drugs like Errin, Jolivette, or Sprintec are technically generics-they went through the ANDA process-but they carry a brand name for marketing. Pharmacists in retail chains often see these as "brand" because of how they’re labeled on shelves. Without clear system indicators, it’s easy to assume a patient wants the "brand" when they actually just want the pill inside.Why Accuracy Matters: Safety, Cost, and Compliance

The U.S. healthcare system saves nearly $2 trillion a decade thanks to generic drugs. But that savings only works if the right drug gets dispensed. If a system defaults to a brand because it can’t tell the difference between an authorized generic and a true brand, patients pay more. Pharmacies lose margins. And insurers get billed incorrectly. But cost isn’t the only concern. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin-tiny differences in absorption can cause serious harm. Systems that auto-substitute without checking TE codes or patient history put lives at risk. A 2021 ISMP report documented 147 adverse events tied to improper generic substitution of warfarin alone. That’s not a glitch. That’s a system failure. Then there’s compliance. Medicare Part D requires pharmacy systems to use Orange Book TE codes with 99.5% accuracy. If they don’t, they risk losing reimbursement. States vary too. California requires pharmacists to document why they didn’t substitute a generic. Texas lets them swap without a word. Systems that don’t adapt to state rules create legal exposure.What the Best Systems Do Differently

The top-performing pharmacy systems don’t just rely on NDCs. They layer in context. Kaiser Permanente’s system, for example, defaults to generic names in all order entry screens. But if a prescriber writes "brand only," the system prompts them to justify it. Patients get a pop-up explaining why generics are safe and cheaper. The result? A 92.7% generic dispensing rate in 2022-with zero drop in patient satisfaction. LexID and Medi-Span, the two biggest drug identification platforms, process billions of transactions yearly with 99.98% accuracy. How? They sync with the FDA’s monthly Orange Book updates and cross-reference with DailyMed, the National Library of Medicine’s drug database. They also track authorized generics by linking NDCs back to the original brand’s New Drug Application (NDA) number. If the NDA holder is the same, the system flags it as "authorized generic"-not just "generic." Even better? Systems now use AI to predict problems. A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association showed AI models could flag potential issues with NTI drugs with 87.3% accuracy by analyzing prescription patterns. If a patient has been on brand levothyroxine for years and suddenly gets switched, the system doesn’t auto-fill. It says: "Hold. Check thyroid levels. Patient history shows sensitivity."

The Hidden Gaps: Inactive Ingredients and Patient Perception

Here’s the part no one talks about enough: generics can have different fillers, dyes, or coatings. The FDA doesn’t require these to match. And while they don’t affect absorption, they can trigger allergies or intolerances. A 2019 study in U.S. Pharmacist found 0.8% of patients on antiepileptic drugs had adverse reactions after switching-likely due to excipients. And then there’s perception. A 2022 Consumer Reports survey showed 89% of patients were satisfied with generics-if they were told why. But 63% were unhappy when substitution happened without explanation. Patients don’t trust what they don’t understand. Pharmacists who don’t have easy access to patient education tools end up answering the same questions over and over. A pharmacy in Dublin, Ireland, recently installed a tablet kiosk next to the pickup counter. It shows a 30-second animated video: "Generic drugs have the same active ingredient, same dose, same safety profile. The only difference? The price." Within three months, brand continuation requests dropped by 41%.What You Can Do: Three Practical Steps

If you work in a pharmacy, here’s how to improve your system’s accuracy:- Update your drug database monthly. The FDA updates the Orange Book every 30 days. If your system hasn’t synced in two months, you’re working with outdated info. Ask your vendor for API integration.

- Train staff on TE codes and authorized generics. A 10-minute huddle once a week can cut confusion. Teach them: "AB" = safe to substitute. "A" before the Appl No. = authorized generic. "B" = not equivalent. No exceptions.

- Build patient education into workflow. Don’t wait for questions. When a generic is dispensed, print a simple slip: "This is the same medicine as [Brand Name]. It’s cheaper. It works the same."

What’s Next: Where the Field Is Heading

The FDA’s 2023 Orange Book modernization is a game-changer. By late 2026, all systems will receive real-time updates via machine-readable API-no more 2-week delays. The 21st Century Cures Act now requires EHRs to clearly label reference listed drugs, authorized generics, and branded generics in structured data fields. That means prescribers will see the difference before they even write the script. And soon, pharmacogenomics will enter the picture. The FDA’s Precision Medicine Initiative is testing whether certain genetic markers predict how a patient responds to a specific manufacturer’s version of levothyroxine. In the future, your pharmacy system might say: "Patient has CYP2D6 variant. Brand only recommended."Final Thought: It’s Not About Brand vs Generic. It’s About Precision.

The goal isn’t to push generics. The goal is to know exactly what’s in the bottle-and why. Whether it’s a brand, an authorized generic, or a branded generic, the system should tell you. The pharmacist should understand it. And the patient should feel confident in it.Because when a pharmacy system gets this right, it’s not just saving money. It’s preventing errors. It’s building trust. And it’s making sure the right pill gets into the right hand at the right time.

Can generic drugs be less effective than brand-name drugs?

No. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also meet strict bioequivalence standards-meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate. Studies show no meaningful difference in effectiveness between properly approved generics and their brand-name counterparts.

Why do some pharmacists hesitate to substitute generics?

Some pharmacists hesitate because of outdated beliefs, patient complaints, or system limitations. For example, if a pharmacy’s software doesn’t clearly flag authorized generics or NTI drugs, staff may default to brand names out of caution. Others worry about patient reactions to different inactive ingredients, especially with epilepsy or thyroid medications. Proper training and clear system alerts reduce this hesitation.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

An authorized generic is made by the original brand-name manufacturer under a separate generic label. It’s chemically identical-same ingredients, same factory, same packaging (except for the label). A regular generic is made by a different company after the patent expires. Both are FDA-approved and bioequivalent, but authorized generics are often more consistent because they come from the same source as the brand.

Are branded generics the same as brand-name drugs?

No. Branded generics are generic drugs that have been given a proprietary name for marketing purposes. They went through the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process, meaning they’re not made by the original brand company. They’re bioequivalent to the brand-name drug but sold under a different name-like Errin instead of Ortho Tri-Cyclen. They’re not the same as the original brand, but they’re still safe and effective.

How do I know if my pharmacy system is up to date with FDA standards?

Check if your system pulls data directly from the FDA’s Orange Book via API and updates weekly. It should display Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) codes (like AB, AO) and clearly distinguish between reference listed drugs, authorized generics, and branded generics. If your system doesn’t show TE codes or requires manual lookup, it’s likely outdated. Ask your vendor for compliance with the 21st Century Cures Act requirements.

Jonah Mann

So i just read this whole thing and like... wow. I work in a pharmacy and honestly? we dont even get trained on TE codes half the time. My system just says "generic" or "brand" and thats it. No flags. No warnings. I had a patient last week get mad because i gave her the "cheap version" of her levothyroxine... turns out it was an authorized generic from the same factory. She didnt even know. I shoulda printed that slip you mentioned. My bad.

Tricia O'Sullivan

Thank you for this meticulously researched and profoundly articulate exposition. The integration of FDA Orange Book data with clinical workflow is not merely a technical necessity, but an ethical imperative. I have observed in Dublin, where I practice, that patient education kiosks reduce anxiety and improve adherence. The 41% reduction in brand requests is not a statistical anomaly-it is a testament to transparency.

Tatiana Barbosa

YES. YES. YES. This is the kind of content that actually makes me want to show up to work. We just rolled out the TE code training last month and holy crap, the number of "why did you switch my med?" calls dropped by 60%. Patients don’t hate generics-they hate being in the dark. Give ‘em a 30-second video and a sticky note? Game changer. Also-authorized generics are the unsung heroes. Stop treating them like second-class citizens. They’re literally the same damn pill.

MANI V

Typical liberal healthcare propaganda. You act like generics are flawless when we all know big pharma pushes them because they’re cheaper, not better. What about the 0.8% who react to excipients? That’s not a glitch-it’s a cover-up. The FDA is in bed with manufacturers. If you’re not prescribing brand-name drugs to every patient, you’re gambling with lives. And don’t even get me started on how they hide the NDA numbers. This system is rigged.

Ryan Vargas

Consider the epistemological framework of pharmaceutical identity. The NDC is not merely a code-it is an ontological marker of pharmaceutical authenticity. When we reduce a drug to a binary of "brand" or "generic," we collapse the nuanced ontologies of production, patent law, and molecular equivalence into a commodified heuristic. The authorized generic, then, is not merely a legal loophole-it is a hermeneutic rupture in the capitalist pharmacopeia. The system’s failure to flag it is not a bug-it is a symptom of late-stage medical capitalism’s inability to comprehend identity beyond transactional value. The patient, in this paradigm, becomes a passive node in a network of obscured provenance. And yet… we still trust the pill. How strange. How tragic. How… human.

Tasha Lake

Quick question-when you say "the system doesn’t flag authorized generics," which systems are you referring to? Epic? Cerner? Are we talking about API sync delays or UI design flaws? Because I’ve seen some pharmacies where the NDA cross-reference is visible if you drill into the product details… just buried under three layers of menus. Is this a training issue or a vendor issue? Asking for a friend who’s trying to fix this at her hospital.

Simon Critchley

Brilliant breakdown. I love how you called out branded generics like Errin-those things are sneaky. I had a patient last week ask for "the blue one" and I thought she meant the brand… turned out she meant the branded generic with the blue capsule. We’ve got a whole wall of pills that look like branded drugs but are ANDA-approved. The marketing teams are winning. We’re just trying to keep up. Also-emoticon needed: 🤯

John McDonald

My team and I just implemented the monthly Orange Book sync. Took 3 days. Worth every second. We now have color-coded flags: green for AB, yellow for AO/AN, red for "brand only" requests. We added a pop-up that says "This is identical to [Brand]" when dispensing authorized generics. Patient complaints? Down 70%. Staff confusion? Gone. This isn’t rocket science-it’s basic diligence. Why isn’t everyone doing this?!

Chelsea Cook

Oh honey. You think the system is the problem? Nah. It’s the people who still think "generic" means "bad." I had a grandma last week refuse her generic blood pressure med because "it’s not the real thing." I showed her the NDA number-same manufacturer, same factory, same bottle design except the label. She cried. Said she’d been taking Zestril since 1998. I gave her a sticker that said "Same Pill. Half the Price." She hugged me. That’s the real win. Not the stats. The hug.

Andrew Jackson

This country has lost its way. We have abandoned quality for cost. The FDA’s modernization efforts are a surrender to global manufacturing interests. The American patient deserves the best-no compromises. If a drug is made in China or India, it should be labeled as such. Not "generic." Not "authorized." We need transparency, not efficiency. We need American-made drugs. Period. This post reads like a corporate white paper from a vendor who profits when we stop asking questions.

John Sonnenberg

This whole thing is a disaster. We're just one system failure away from a national crisis. And nobody's talking about it. Nobody. Just... nobody.