Liver Disease Opioid Dosing Calculator

Safe Opioid Dosing Calculator

Calculate adjusted opioid doses based on liver disease severity using Child-Pugh classification. The calculator applies evidence-based guidelines from the article.

Adjusted Dose Recommendation

mg

Adjustment:

When your liver is damaged, taking opioids isn’t just riskier-it can be dangerous in ways most people don’t expect. Opioids like morphine and oxycodone are designed to be broken down by the liver. But when that organ is struggling due to cirrhosis, fatty liver disease, or hepatitis, those drugs don’t clear the way they should. Instead, they build up. And that buildup doesn’t just mean stronger pain relief-it means a much higher chance of overdose, confusion, breathing problems, and even death.

How the Liver Normally Handles Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to process opioids: cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are like factory assembly lines that break down drugs into smaller pieces so your body can flush them out through urine or bile. Morphine, for example, gets turned into two main metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which helps with pain, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which can cause seizures and confusion. Normally, your liver keeps these in balance. But when liver function drops, that balance collapses.

Oxycodone works differently. It’s broken down mainly by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes. In a healthy person, it clears out in about 3.5 hours. But in someone with severe liver disease, that time can stretch to 14 hours-or even longer. Studies show peak blood levels of oxycodone can jump by 40% in advanced liver failure. That’s not a small change. It’s the difference between a safe dose and a toxic one.

Why Liver Disease Changes Everything

Liver disease isn’t one condition. It’s a spectrum. A person with early-stage non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may have slightly reduced CYP3A4 activity. Someone with advanced cirrhosis from alcohol use might have suppressed CYP3A4 but *increased* CYP2E1 activity, which can turn some opioids into more toxic forms. The same drug can behave differently depending on what’s causing the liver damage.

What’s worse, opioids don’t just rely on the liver-they can hurt it too. Chronic use changes the gut microbiome, leading to inflammation that travels straight to the liver through the gut-liver axis. This creates a vicious cycle: liver damage slows opioid clearance, and opioids make liver damage worse. In people with hepatitis C or alcoholic liver disease, this interaction can accelerate scarring and increase the risk of liver failure.

Which Opioids Are Riskiest?

Not all opioids are created equal when the liver is damaged.

- Morphine: High risk. Its metabolites stick around longer and build up. Even mild liver impairment requires lower doses. In severe cases, the same dose can cause coma.

- Oxycodone: Also high risk. Starting doses should be cut to 30%-50% in severe liver disease. Many doctors still prescribe standard doses-this is a common and dangerous mistake.

- Methadone: Metabolized by multiple enzymes, so it’s theoretically safer. But there are no clear dosing guidelines for liver patients. That lack of data makes it risky to use without expert supervision.

- Fentanyl and buprenorphine: These are metabolized differently. Fentanyl is cleared mostly by the liver but has a short half-life. Buprenorphine is partly cleared by the liver and partly by the kidneys. Transdermal patches (like fentanyl patches) avoid first-pass liver metabolism, making them a better option for some patients.

A 2023 systematic review confirmed that opioid-related side effects-like sedation, respiratory depression, and delirium-are 2 to 3 times more common in people with liver disease than in healthy individuals. The reason? Reduced Phase I metabolism. That’s the liver’s first step in breaking down drugs. When that step slows, everything downstream goes wrong.

Dosing Adjustments That Actually Work

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule, but here’s what experts recommend based on real-world data:

- For mild liver disease (Child-Pugh A): Reduce opioid dose by 25%-50%. Keep dosing intervals the same.

- For moderate to severe disease (Child-Pugh B or C): Reduce dose by 50%-75%. Also increase the time between doses. For example, if you normally take oxycodone every 4 hours, switch to every 8 hours.

- Avoid morphine entirely in Child-Pugh C patients. The risk of M3G toxicity is too high.

- Start low, go slow. Never assume a patient’s tolerance level. Even if they’ve used opioids before, their liver might not handle it the same way now.

- Monitor closely. Watch for drowsiness, slurred speech, slow breathing, or confusion. These aren’t just side effects-they’re warning signs of opioid toxicity.

One real case from a Manchester hospital in 2024 involved a 62-year-old man with alcohol-related cirrhosis. He was prescribed 10 mg of oxycodone every 6 hours for back pain. Within 48 hours, he became lethargic and stopped breathing. His blood level of oxycodone was nearly 5 times higher than normal. He survived, but only because his family noticed the change early. This isn’t rare. It’s predictable.

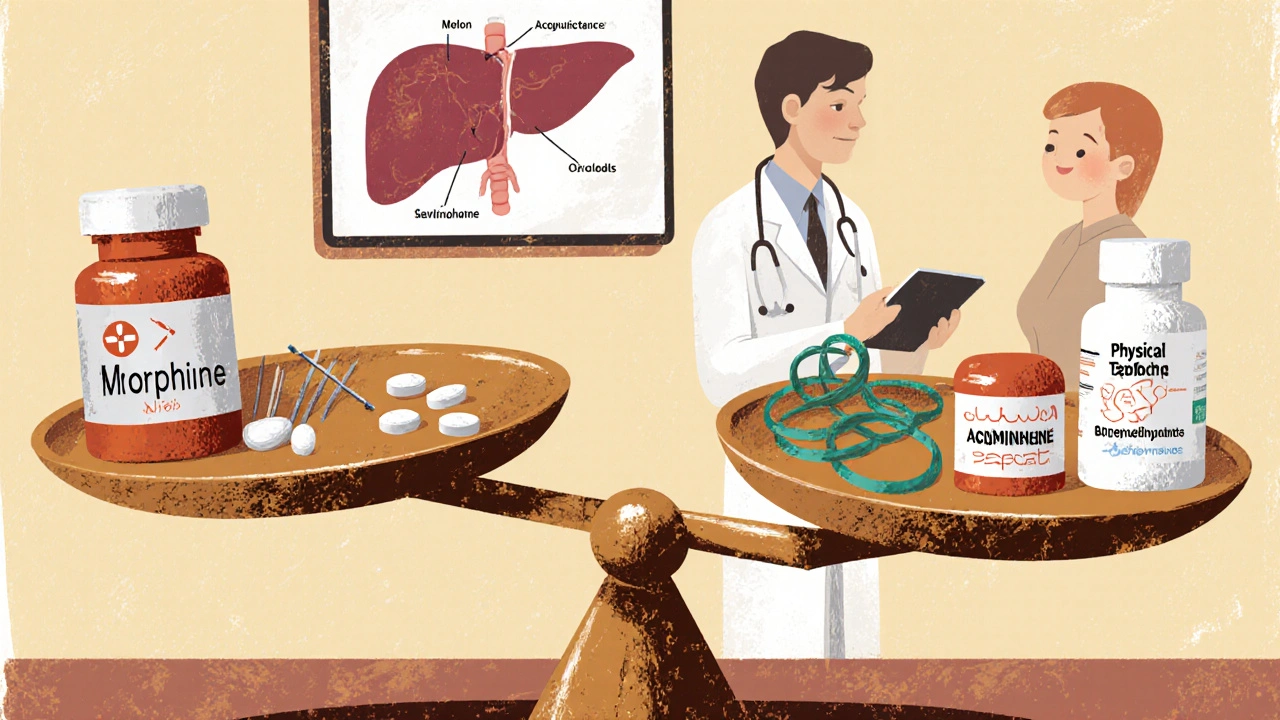

What About Alternatives?

Non-opioid pain relief should be the first choice in liver disease. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is often avoided because of liver risks-but in low doses (up to 2 grams per day), it’s generally safe for most patients with stable liver disease. NSAIDs like ibuprofen are risky due to kidney strain and bleeding, so they’re not ideal either.

Non-drug options matter too. Physical therapy, nerve blocks, cognitive behavioral therapy, and even acupuncture can reduce opioid needs. For chronic pain, a multidisciplinary approach is the safest path. If opioids are unavoidable, transdermal patches (buprenorphine or fentanyl) are often better than pills because they avoid the liver’s first-pass effect.

The Big Gaps in Knowledge

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we don’t know enough. There are no large, well-designed studies on how to dose opioids safely in patients with NAFLD, autoimmune hepatitis, or early-stage cirrhosis. Guidelines are based on small studies, expert opinion, and extrapolation from healthy people.

We also don’t have clear data on long-term opioid-induced liver injury. Does long-term morphine use worsen fibrosis? Does buprenorphine protect the liver because it’s a partial agonist? These questions remain unanswered. Until we have better data, caution is the only safe policy.

What Patients Should Ask Their Doctor

If you have liver disease and are prescribed an opioid, ask these questions:

- Is this the safest opioid for my type of liver damage?

- What dose should I start with, and why?

- Should I take it less often than normal?

- What signs of toxicity should I watch for?

- Are there non-opioid options I haven’t tried yet?

Don’t be afraid to push back. Many patients assume their doctor knows the right dose. But the truth is, most clinicians aren’t trained in liver-specific opioid pharmacology. Your safety depends on you asking the right questions.

Final Takeaway

Opioids aren’t inherently bad. But in liver disease, they become a minefield. The same drug that helps one person can harm another-because of how their liver works. The key isn’t avoiding opioids entirely. It’s using them smarter. Lower doses. Longer gaps. Closer monitoring. And always, always considering alternatives first.

If your liver is damaged, your body doesn’t process drugs the same way. That’s not a flaw-it’s biology. And respecting that biology could save your life.

Idolla Leboeuf

Just had my mom on buprenorphine patches for her cirrhosis and chronic back pain. No more hospital trips. No more confusion. She says she feels like herself again. Doctors need to stop treating liver patients like they’re just broken opioids machines. This post? Lifesaver.

Matthew Williams

Oh great, another liberal guilt-trip disguised as medical advice. People are dying from overdoses because they’re weak, not because doctors prescribed morphine. Stop coddling addicts with liver damage. Just say no. That’s the real solution.

Dave Collins

Oh wow, a 2023 systematic review? How quaint. I read a paper in The Lancet that said the same thing in 2018. Honestly, if you’re still using morphine in cirrhosis, you’re not a doctor-you’re a time traveler from 1997.

Terri-Anne Whitehouse

Let’s be honest-this whole opioid conversation is a statistical illusion. The liver metabolizes drugs differently, sure, but we’re ignoring the elephant in the room: pharmaceutical companies pushed these meds for decades. Now we’re blaming the patient’s biology instead of the profit-driven prescribing culture. M3G toxicity? That’s not a pharmacokinetic quirk-it’s a corporate crime.

And don’t get me started on how ‘low-dose acetaminophen’ is suddenly safe. The FDA’s own data shows even 1.5g/day can spike ALT in NAFLD patients. But hey, let’s keep pretending this is just about ‘dosing’ when it’s really about who gets to live and who gets written off.

I’ve seen three patients in the last year with Child-Pugh C die after being prescribed ‘standard’ oxycodone. Their charts all said ‘tolerant.’ Their labs said ‘failing.’ Their doctors? Too busy to check. We’re not talking about medical nuance here. We’re talking about negligence dressed up as science.

And then there’s the myth that buprenorphine is ‘safer.’ It’s not. It’s just slower to kill you. The transdermal patch avoids first-pass? Great. But it also avoids monitoring. No one checks blood levels. No one asks if the patient’s still breathing. And when they don’t wake up? ‘Oh, must’ve been the cirrhosis.’

Meanwhile, the real solution-pain clinics, PT, CBT-is underfunded, understaffed, and buried under insurance bureaucracy. We’d rather keep writing scripts than fix the system. So yes, lower the dose. But also stop pretending this is a medical problem. It’s a moral one.

Cole Brown

Hey, if you or someone you love has liver issues, please just talk to your doctor before changing anything. Start low, go slow. Watch for drowsiness. Don’t be shy to ask for alternatives. You deserve to be safe. I’ve been there. It’s scary, but you’re not alone.

Danny Pohflepp

According to the CDC’s 2022 opioid surveillance report, 68% of opioid-related deaths in patients with liver disease occurred within 72 hours of a dose increase or new prescription. Meanwhile, the NIH’s 2023 funding allocation for hepatotoxicity research was $12.7 million-0.03% of total opioid research spending. This is not an oversight. It is a targeted systemic erasure of vulnerable populations under the guise of ‘clinical ambiguity.’ The pharmaceutical lobbying arms-Purdue, Teva, Mallinckrodt-have spent $2.1 billion since 2015 to suppress dosing guidelines. The data exists. It’s being buried.

Halona Patrick Shaw

I used to work in a pain clinic in rural Ohio. Saw a guy on 80mg oxycodone a day with alcoholic cirrhosis. He didn’t even know his liver was failing. His wife said he’d been ‘just tired’ for months. We switched him to fentanyl patch, cut the dose by 70%, added physical therapy. Six weeks later-he was playing with his grandkids again. No coma. No ER. Just… life. This isn’t just medical advice. It’s a second chance.

Nate Barker

So basically, don’t take painkillers if you drink. Got it.

charmaine bull

the fact that we dont have clear guidelines for nafld patients is wild. i had a friend on methadone for 3 years with fatty liver and no one ever monitored her metabolites. she just kept getting more tired. we only found out when her bilirubin spiked. i think this needs to be a public health emergency.

Torrlow Lebleu

Anyone who takes opioids with liver disease is just asking for trouble. You knew the risks when you started drinking or eating junk food. Now you want the system to bend over backward? Sorry, biology doesn’t care about your excuses. Cut the dose? Cut the habit. End of story.

Christine Mae Raquid

I can’t believe people are still dying from this. My cousin was on morphine for cancer pain and had cirrhosis from hepatitis C. They didn’t adjust the dose. She went to sleep and never woke up. I still cry every time I see a pill bottle. This is preventable. Why aren’t we screaming about it?

Sue Ausderau

It’s not about avoiding pain. It’s about honoring the body’s limits. When the liver is damaged, it’s not broken-it’s trying to survive. Maybe the real medicine isn’t the drug, but the humility to listen to what the body is telling us.

Tina Standar Ylläsjärvi

Biggest takeaway: if you have liver disease and need pain help, ask your doctor about physical therapy, nerve blocks, or even acupuncture. I used to think those were ‘woo-woo’-until my dad tried it. He cut his oxycodone by 80% and stopped feeling foggy all day. Real healing isn’t always a pill.