When you're fighting cancer, every dose matters. Not just the amount, but how your body absorbs it, how it interacts with other drugs, and whether the generic version you're given works just like the brand-name one. This isn't theoretical-it's life or death. And when multiple cancer drugs are combined, the rules change completely. The bioequivalence standards that work for a single pill? They don't cut it for combination regimens. That’s where things get messy, expensive, and risky.

Why Bioequivalence Matters in Cancer Treatment

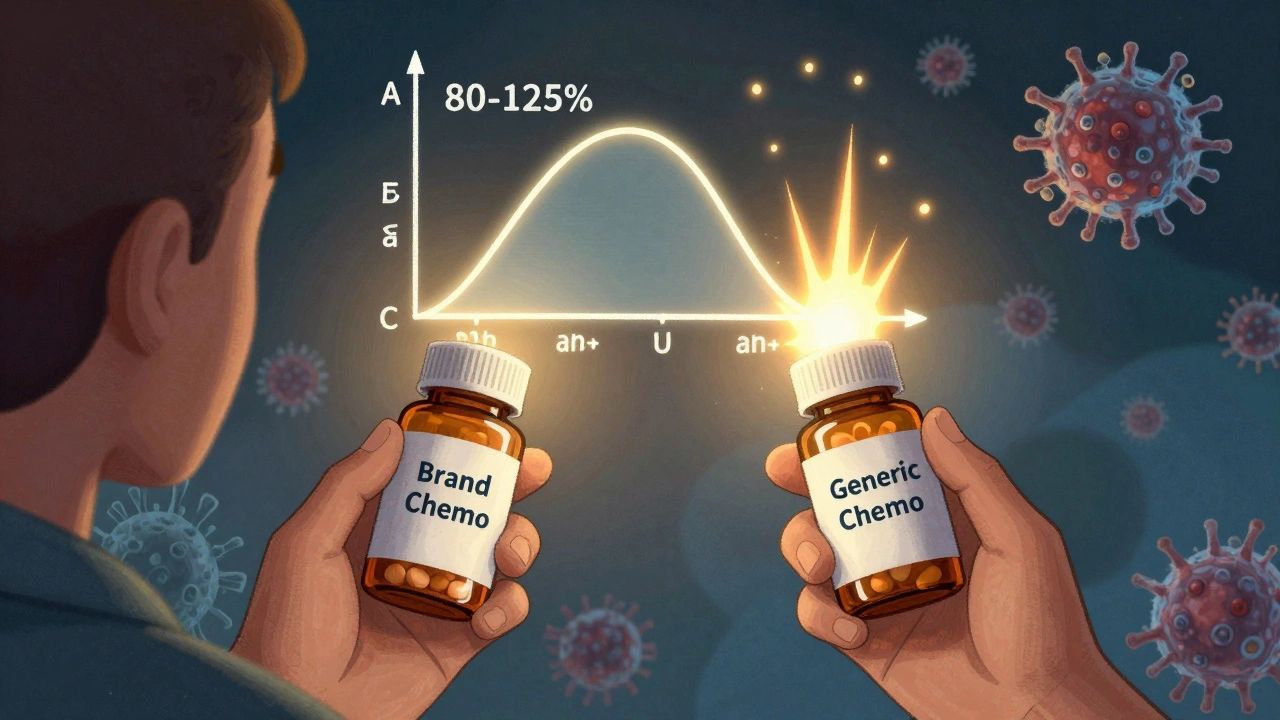

Bioequivalence means two drugs deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed. For most medications, if a generic passes this test, it’s considered safe to swap. But cancer drugs? They’re different. Many have a narrow therapeutic index, meaning the difference between a dose that works and one that’s toxic is tiny. A 5% difference in absorption might mean the drug fails to kill cancer cells-or it could wreck your bone marrow. The FDA and EMA require generic drugs to show that their AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration) fall within 80-125% of the brand-name version. That’s fine for a blood pressure pill. For chemo? It’s not enough. Dr. James McKinnell from Johns Hopkins pointed out at the 2023 ASCO meeting that for drugs like methotrexate used in combinations, the margin should be tighter: 90-111%. Yet most generics still only need to meet the standard range.Single-Agent vs. Combination Regimens: The Big Divide

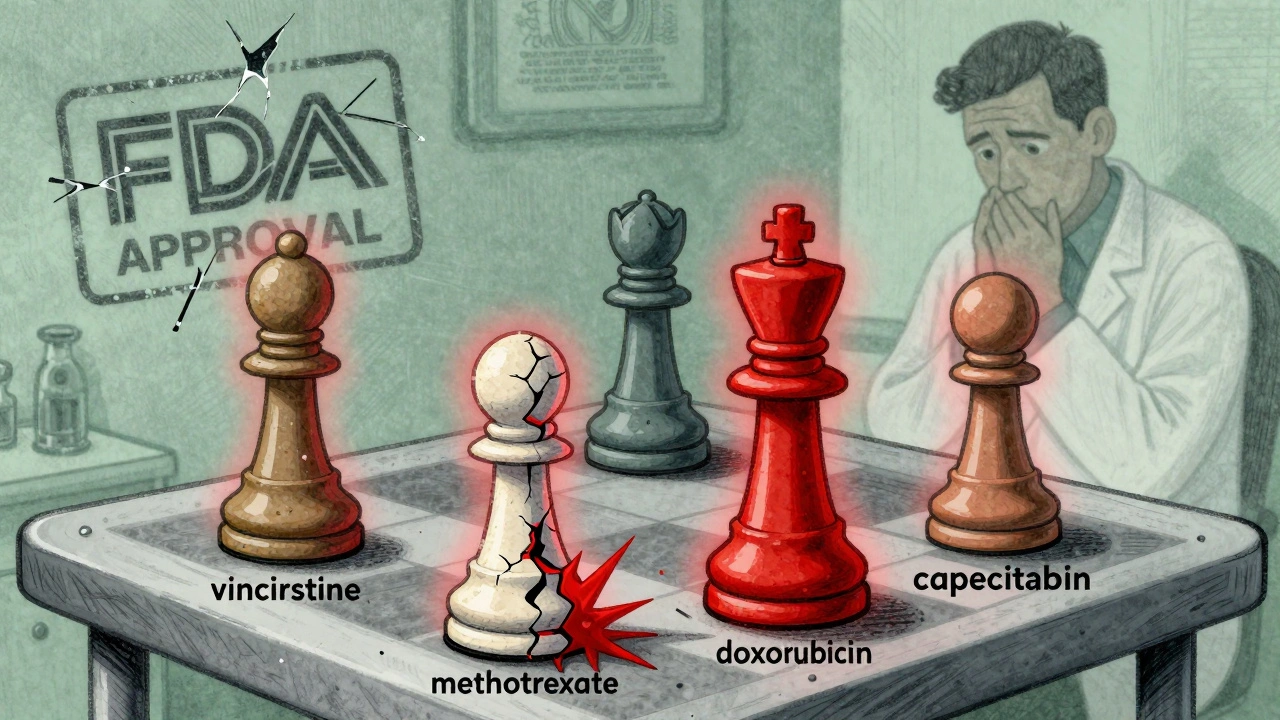

Most cancer treatments today use combinations. About 70% of protocols involve two or more drugs. Think FOLFOX (5-FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) for colorectal cancer, or R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) for lymphoma. Each component has to be bioequivalent. But here’s the catch: when you swap one generic component, you change how the whole mix behaves. A 2023 study from the Gulf Cancer Consortium found 42% of oncologists worried about substitution in combination therapies, compared to just 15% for single agents. Why? Because drug interactions shift. One generic version of vincristine might have a slightly different coating, changing how fast it dissolves. That alters peak levels. When paired with another drug that’s already at its limit, that small shift can trigger severe nerve damage-or let cancer slip through. A real case from the ASCO Community Forum showed a patient on R-CHOP developed unexpected neuropathy after a pharmacy switched to a different generic vincristine. The brand and other generics were fine. But this one? It spiked plasma concentrations just enough to cause harm. No one saw it coming because bioequivalence studies only looked at the individual drug, not the combo.The Biologic Problem: Biosimilars Aren’t Bioequivalent

Not all cancer drugs are pills. Many are biologics-complex proteins like trastuzumab (Herceptin) or rituximab (Rituxan). These can’t be copied like small-molecule drugs. Instead, you get biosimilars. And biosimilarity isn’t bioequivalence. It’s a different standard. Biosimilars must show no meaningful difference in safety, purity, or potency through clinical trials. But even then, switching between biosimilars and originators in combination regimens is risky. Generic trastuzumab biosimilars have saved $6,000-$10,000 per cycle with no loss in survival. That’s huge. But when you combine a biosimilar with a generic chemo drug, you’re stacking two variables. The FDA doesn’t require testing the combo. Hospitals assume it’s safe. But 68% of hospital formulary committees demand extra clinical data before approving substitutions in these cases. And they’re right to.

What Happens When Generics Are Swapped

A 2023 survey of 250 U.S. oncology pharmacists found 57% had seen cases where swapping one generic component led to unexpected toxicity or reduced effectiveness. Most of these involved narrow therapeutic index drugs: vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine, or doxorubicin. The problem isn’t always the drug itself-it’s the formulation. Different fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes can change how quickly the drug releases in the gut or bloodstream. At MD Anderson, a study of 1,247 patients using generic capecitabine instead of Xeloda in combination with oxaliplatin showed nearly identical survival and side effects. That’s the success story. But it’s rare. Why? Because capecitabine is an oral drug with a wide therapeutic window. It’s forgiving. Vincristine? Not so much. Patients notice too. A 2024 survey by Fight Cancer found 63% of patients were worried about generic substitution in combination therapy. Over 40% said they’d ask for brand-name drugs if they could afford it-even though 82% knew generics saved money. Trust isn’t just about cost. It’s about fear.How Regulators Are Responding

The FDA is starting to catch up. In 2024, they launched the Oncology Bioequivalence Center of Excellence. Their goal? To create new testing standards for combination products. They’re also testing physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling-computer simulations that predict how drug interactions change when generics are swapped. It’s promising. The EMA is even stricter. For high-risk combinations, they now require full clinical endpoint studies-not just blood levels. If a combo affects survival or progression, you need to prove the generic doesn’t hurt those outcomes. That’s expensive. It’s why many generic makers avoid oncology combos altogether. The International Consortium for Harmonisation of Bioequivalence Standards in Oncology released new guidelines in March 2024. They recommend tighter margins (90-111%) for narrow index drugs in combinations and mandatory food-effect studies for all oral components. That’s a big step. But it’s not law yet.

What Hospitals Are Doing Differently

Some institutions are taking control. The University of California, San Francisco built a decision support tool that flags combination regimens with high-risk components. When a pharmacist tries to substitute a generic, the system alerts them if any drug in the combo has a narrow therapeutic index. It cut inappropriate substitutions by 63%. The Gulf Cooperation Council developed a scoring system that weighs 12 factors: manufacturing quality (30%), regulatory alignment (25%), cost (20%), supply reliability (15%), and patient trust (10%). It’s not perfect, but it’s better than just picking the cheapest option. Oncology pharmacy residencies now include over 40 hours of training on combination bioequivalence. That’s new. Five years ago, most pharmacists learned nothing about this. Now, they’re being taught to read between the lines of bioequivalence studies-and ask the right questions.The Cost of Waiting

The global market for generic oncology drugs hit $38.7 billion in 2023. That’s 42% of all cancer drug spending. By 2027, it’s projected to hit $52.3 billion. Branded drugs cost $150,000 a year per patient. Generics? Around $45,000. The American Cancer Society estimates the U.S. could save $14.3 billion a year if generics were used safely in combinations. But that only works if we fix the system. Right now, we’re playing Russian roulette with patient outcomes. We allow substitutions based on outdated standards. We assume that if each drug works alone, the combo will too. But biology doesn’t work that way.What Needs to Change

We need three things:- Combo-specific bioequivalence studies-not just individual drugs, but the whole regimen tested together.

- Tighter margins for narrow therapeutic index drugs in combinations: 90-111%, not 80-125%.

- Transparency-hospitals and patients need to know exactly which generic version is being used and why.

Cost savings matter. But not at the cost of survival.

Can generic cancer drugs be safely substituted in combination therapy?

It depends. For simple combinations with wide therapeutic index drugs like capecitabine, yes-studies show equivalent outcomes. But for regimens with narrow index drugs like vincristine, methotrexate, or doxorubicin, substitution carries risk. Even minor differences in absorption can trigger toxicity or reduce efficacy. Most experts recommend avoiding substitution unless the entire combination product has been tested as a unit.

Why aren’t all cancer combination generics approved as fixed-dose combinations?

Because manufacturers often avoid it. Developing a fixed-dose combo requires new clinical trials and regulatory approval for each unique combination. It’s expensive and time-consuming. Instead, pharmacies compound generics from individual pills-which is legal but risky. The FDA only requires bioequivalence for each component, not the final mix. That’s why drug interactions and absorption changes go untested.

Are biosimilars the same as generic cancer drugs?

No. Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are highly similar versions of complex biologics like monoclonal antibodies. They’re not interchangeable by default. Biosimilars require clinical studies to prove safety and potency, but even then, switching between biosimilars and originators in combination regimens isn’t guaranteed safe. Regulatory agencies treat them differently, and so should clinicians.

How do I know if my cancer meds are generic or branded?

Ask your pharmacist or oncology team. Generic versions often have different names or pill markings. The FDA’s Orange Book lists therapeutically equivalent products with an "A" rating. But for combination regimens, an "A" rating for each component doesn’t mean the combo is safe to swap. Always check the exact formulation and manufacturer-especially if you’ve had side effects after a recent change.

What should patients do if they’re concerned about generic substitution?

Speak up. Request the original brand-name combination if available and affordable. If cost is an issue, ask if a fixed-dose combo version exists. Never accept a substitution without knowing which generic version is being used. Keep a record of side effects after any change. If you notice new nerve pain, fatigue, or reduced effectiveness, report it immediately. Your feedback helps build the evidence needed to change the system.

Chelsea Moore

Let me get this straight-we’re letting pharmacies swap life-saving chemo drugs like they’re swapping out laundry detergent?!! This isn’t just negligence, it’s criminal. I’ve seen friends lose their hair, then lose their lives, because some pharmacist thought ‘close enough’ was good enough. Where’s the accountability?! Someone needs to go to jail for this.

John Morrow

The fundamental flaw in the current regulatory paradigm lies in its reductionist epistemology-treating pharmacokinetic variables as isolated, linear entities when, in reality, the pharmacodynamic interplay within multi-agent oncologic regimens constitutes a nonlinear, high-dimensional system. The 80–125% bioequivalence threshold, derived from cardiovascular or psychiatric pharmacology, is epistemologically incommensurate with the narrow therapeutic index and synergistic toxicity profiles inherent to cytotoxic combinations. Until regulatory bodies adopt systems pharmacology models and mandate combinatorial PBPK validation, we are not merely tolerating risk-we are institutionalizing it.

Kristen Yates

I work in a hospital pharmacy. We don’t substitute vincristine generics unless the oncologist signs off and we document the batch number. It’s not about cost. It’s about knowing that one tiny change can mean a patient spends their last weeks in the ER instead of at home. I’ve seen it. It’s not worth the risk.

Saurabh Tiwari

bro this is wild but also kinda obvious 🤷♂️ i mean if you mix two drugs and one changes how fast it dissolves... of course the whole thing acts different. why are we even surprised? we do this with coffee and painkillers and get weird side effects. cancer drugs? same deal. just way more serious. we need better testing. not more paperwork. more science.

Michael Campbell

FDA’s asleep at the wheel. Big Pharma owns them. Why do you think they let this slide? Because generics cost less and they don’t want to lose profits. We’re just guinea pigs for their profit margins. And don’t even get me started on India making these pills-no quality control. My cousin died because of a generic. It was murder.

Victoria Graci

There’s something haunting about how we treat cancer drugs like interchangeable parts in a machine. We don’t swap out a heart valve and assume the body won’t notice. Why do we assume a drug’s molecular soul can be replicated without consequence? The body doesn’t care about FDA guidelines or cost savings. It responds to chemistry. And when that chemistry shifts-even slightly-it doesn’t whisper. It screams. And too often, the scream comes too late.

Saravanan Sathyanandha

This is not just a regulatory issue-it is a moral one. In India, we see families choosing between treatment and feeding their children. Generics save lives. But if we do not ensure their safety in combinations, we are trading one tragedy for another. We must push for global standards that are both rigorous and compassionate. Science must serve humanity, not corporate convenience.

alaa ismail

i’ve been on chemo. switched generics once. felt like i was getting hit by a truck for a week. doc said it was ‘just side effects.’ i knew better. never switched again. cost doesn’t matter if you’re dead.

ruiqing Jane

To every pharmacist, oncologist, and policymaker reading this: you hold the power to protect lives. Don’t let convenience override caution. Don’t let budget lines dictate biological outcomes. Every patient deserves the certainty that their treatment is as precise as it was designed to be. Your silence is complicity. Speak up. Document. Advocate. Change begins with one voice.

Fern Marder

i mean... 🤔 why do we even let pharmacies do this? it’s like letting someone swap your car’s engine with a ‘close enough’ knockoff and then saying ‘it runs, right?’ also, biosimilars ≠ generics. stop mixing them up. it’s like comparing a hand-painted portrait to a photocopy. 🎨❌📄

Allan maniero

The real tragedy isn't the lack of regulation-it's the normalization of risk. We’ve become so accustomed to cost-cutting in healthcare that we’ve forgotten what it means to heal. Oncology isn’t a commodity. It’s a covenant between patient and provider. When we substitute without understanding, we break that covenant. And no spreadsheet can quantify the cost of broken trust.

Anthony Breakspear

Look-I get it. Money’s tight. Hospitals are stretched thin. But here’s the thing: you don’t save money by risking someone’s life. You just delay the bill. A patient who has a bad reaction ends up in the ICU for weeks. A missed dose lets cancer spread. That costs way more than sticking with the brand. Smart hospitals already know this. They’re the ones with lower readmission rates. It’s not about being expensive-it’s about being smart.

Zoe Bray

Current bioequivalence paradigms are predicated upon single-agent pharmacokinetic profiles, which are fundamentally inadequate for multi-drug combination regimens characterized by nonlinear pharmacodynamics, competitive protein binding, and metabolic enzyme modulation. The absence of combinatorial therapeutic equivalence validation constitutes a critical gap in evidence-based oncology practice. Regulatory frameworks must evolve to incorporate population pharmacokinetic modeling and real-world outcome surveillance to mitigate iatrogenic harm.

Girish Padia

india makes 80% of the world's generics. if you think this is bad here, you should see what’s happening in africa and latin america. no one checks. no one cares. people die. and the big companies? they just move on to the next market. this isn’t about science. it’s about greed.