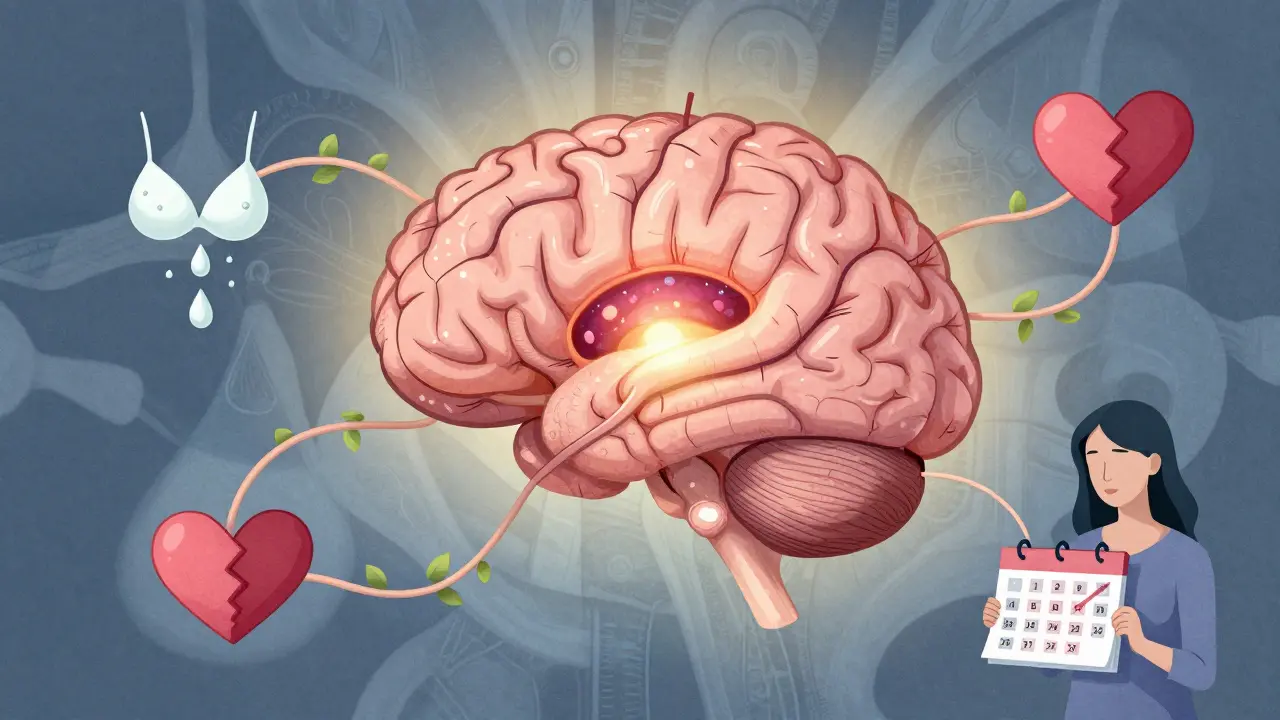

When your body’s main hormone control center starts growing a benign tumor, things don’t always show up on a radar screen. Most people with pituitary adenomas never know they have one-until symptoms like irregular periods, low sex drive, or unexplained milk production force a closer look. These tumors, especially the most common type called prolactinomas, don’t spread like cancer. But they mess with your hormones in ways that ripple through your whole life.

What Exactly Is a Prolactinoma?

A prolactinoma is a non-cancerous growth in the pituitary gland that makes too much prolactin. This hormone normally tells your body to make breast milk after childbirth. But when it’s overproduced, it shuts down other key hormones like estrogen and testosterone. In women, this leads to missed periods, trouble getting pregnant, and even milk leaking from the breasts when they’re not nursing. In men, it causes low libido, erectile dysfunction, and sometimes breast tenderness or enlargement. About 40 to 60% of all pituitary tumors are prolactinomas, making them by far the most common type.

Size matters here. Most prolactinomas are small-under 1 centimeter-and called microadenomas. These often cause only hormone problems. But when they grow larger than 1 cm (macroadenomas), they start pressing on nearby structures. That’s when vision problems can happen, especially loss of peripheral vision, because the tumor pushes against the optic nerve. About 20% of all pituitary tumors are this size, and prolactinomas are the most likely to grow big.

How Do You Know You Have One?

It starts with a blood test. If your prolactin level is over 150 ng/mL, there’s a 95% chance it’s a prolactinoma. Levels above 200 ng/mL almost always mean a larger tumor. But don’t jump to conclusions-some medications, stress, pregnancy, or even a full stomach can temporarily raise prolactin. Your doctor will check for those first.

Then comes the MRI. A high-resolution scan of your brain, with 3mm slices, shows the exact size and position of the tumor. If it’s bigger than 1 cm, you’ll also need a visual field test. This checks if your peripheral vision is being squeezed by the tumor. It’s simple: you sit in front of a machine and press a button when you see a flash of light in your side vision. Missing spots? That’s a red flag.

What makes prolactinomas different from other pituitary tumors? They’re the only ones that usually respond dramatically to pills. Other hormone-secreting tumors-like those making too much cortisol or growth hormone-often need surgery or radiation. But prolactinomas? They’re the most treatable.

The First-Line Treatment: Dopamine Agonists

For most people, the first and only treatment needed is a pill. Two drugs are used: cabergoline and bromocriptine. Cabergoline is the clear winner. It’s taken just twice a week, works better, and causes fewer side effects. Bromocriptine needs to be taken daily and often causes nausea, dizziness, or fainting-so many people quit taking it.

Doctors usually start with 0.25 mg of cabergoline twice a week. After a month, they check your prolactin level. If it’s still high, they bump it up to 0.5 mg or even 1 mg twice a week. Most people see prolactin drop into the normal range within three months. Tumors shrink too-up to 85% of cases show noticeable reduction. One patient in her early 30s saw her prolactin level plunge from 5,200 ng/mL to just 18 ng/mL in six months. Her tumor shrank by 70%. She’s now pregnant.

But here’s the catch: you might need to stay on these pills for years-even lifelong. About 70% of patients can’t stop without prolactin bouncing back. Stopping suddenly causes levels to spike within 72 hours. That’s why regular blood tests every 3 months are critical, at least at first.

When Surgery Becomes Necessary

Surgery isn’t the first choice for prolactinomas. But it’s needed if the tumor is pressing on your optic nerves and threatening your vision, or if you can’t tolerate the pills. The procedure is called transsphenoidal surgery. It’s done through the nose, no scalp incision. Endoscopic tools give surgeons a clear view, and recovery is quick-most people go home in 3 to 5 days.

Success rates? They depend on size. For small tumors, surgeons cure the problem in 85 to 90% of cases. For large ones, it drops to 50-60%. Why? Because big tumors often grow into the cavernous sinus, wrapping around major arteries and nerves. You can’t safely remove all of it without risking stroke or blindness.

Post-surgery, some people develop temporary diabetes insipidus-excessive thirst and urination-because the pituitary’s antidiuretic hormone gets disrupted. It’s treated with desmopressin and usually clears up in weeks. Other risks include CSF leaks (2-5%) or pituitary apoplexy (1-2%), where the tumor bleeds suddenly. These are rare, but serious.

Radiation Therapy: A Last Resort

Radiation is rarely used for prolactinomas anymore. It’s slow. It can take 2 to 5 years to lower hormone levels. And it often damages the pituitary gland over time, leading to lifelong hormone replacement for cortisol, thyroid, or sex hormones. About 30-50% of patients develop hypopituitarism within 10 years after radiation.

Still, it has its place. If a tumor comes back after surgery and pills don’t work, or if someone can’t have surgery, radiation is an option. Gamma Knife radiosurgery is the preferred method-it delivers a precise, high-dose beam in a single session. It controls tumor growth in 95% of cases and has a 1-2% risk of damaging the optic nerve, compared to 5-10% with traditional radiation.

Long-Term Risks and Monitoring

Long-term cabergoline use-especially doses over 2.5 mg per week for more than three years-carries a small risk of heart valve damage. That’s why the European Society of Endocrinology recommends an echocardiogram every two years for patients on high doses. It’s rare, but real. The FDA added a black box warning for this in 2021.

Even if your tumor shrinks and your prolactin normalizes, you still need annual checkups. Hormone levels can drift. The pituitary gland might not fully recover. And new tumors can form, especially if you have a genetic condition like MEN1 syndrome.

There’s also the emotional toll. People with prolactinomas often feel isolated. Fertility issues, sexual dysfunction, and body changes can affect relationships and self-esteem. Support groups, like those on Reddit’s r/pituitary, help. One patient wrote: “I thought I was broken. Turns out, I just had a tumor. And it was fixable.”

What’s Next for Treatment?

The future is looking promising. A new drug called paltusotine, originally for acromegaly, is now being tested for prolactinomas. It’s taken orally and might offer another option for people who can’t tolerate cabergoline. Researchers are also exploring CRISPR gene editing to target mutations like GNAS and USP8 that drive tumor growth. AI is being used to map tumor shapes during surgery, helping surgeons avoid nerves.

One big shift: doctors are starting to test tumors for molecular markers before deciding on treatment. In five years, we might not just treat based on size and prolactin level-we’ll treat based on the tumor’s DNA. That could raise cure rates from 70% to 90%.

But for now, the message is simple: if you have unexplained symptoms like missed periods, low libido, or milk production, get your prolactin checked. Most prolactinomas are found late because they’re silent. But they’re also among the most treatable tumors in the body. With the right diagnosis and medication, most people go on to live full, healthy lives.

Can a prolactinoma cause infertility?

Yes. High prolactin levels suppress the hormones needed for ovulation in women and sperm production in men. In women, this leads to amenorrhea and anovulation. In men, it lowers testosterone and reduces sperm count. But in most cases, fertility returns once prolactin levels are normalized with medication. Many women who couldn’t conceive for years become pregnant after starting cabergoline.

Can you stop taking cabergoline after your tumor shrinks?

Sometimes, but rarely. About 30% of people with microprolactinomas can stop medication after 2-3 years of normal prolactin levels and no tumor on MRI. But for most, especially those with larger tumors, stopping leads to a rebound in prolactin and tumor regrowth within months. Doctors usually recommend staying on low-dose cabergoline indefinitely unless there’s clear, long-term stability.

Does a prolactinoma affect men differently than women?

Yes. Women often notice symptoms sooner because of missed periods or breast milk. Men’s symptoms-low sex drive, erectile dysfunction, fatigue-are more subtle and often blamed on stress or aging. As a result, men are diagnosed later, often only after vision problems appear. The tumor size at diagnosis is typically larger in men. But treatment works equally well in both genders.

Is surgery dangerous for prolactinomas?

Transsphenoidal surgery is generally safe, especially when done by experienced teams. The biggest risks are temporary diabetes insipidus (5-10%), CSF leaks (2-5%), and pituitary hormone deficiencies. Permanent damage to the pituitary occurs in less than 5% of cases. The risk of stroke or blindness is under 1%. Success rates are high for small tumors (85-90%) but drop significantly for large, invasive ones.

Can prolactinomas turn cancerous?

No. Pituitary adenomas, including prolactinomas, are benign by definition. They don’t metastasize. But they can grow aggressively and invade nearby bone or tissue-especially if untreated. This is called invasive adenoma, not cancer. Still, they’re not harmless. Left unchecked, they can cause permanent vision loss or hormone failure.

matthew martin

Man, I never realized how many people walk around with these silent little time bombs in their heads. I had a buddy whose prolactin was through the roof for years-he thought he was just "getting old" until his vision started going. Got diagnosed after a migraine. Now he’s on cabergoline, got his libido back, and just became a dad. Crazy how one blood test changes everything.

And yeah, the fact that you can shrink a brain tumor with a pill twice a week? That’s sci-fi level medicine. I’m just glad we’re not stuck with cutting skulls open for everything anymore.

Jeffrey Carroll

The clinical management of prolactinomas represents one of the most successful examples of targeted pharmacological intervention in neuroendocrinology. The efficacy of dopamine agonists, particularly cabergoline, in normalizing hormonal profiles and inducing tumor regression is well-documented in peer-reviewed literature, with response rates exceeding 80% in microadenoma cases. Long-term surveillance remains essential, as recurrence following discontinuation is common, particularly in macroprolactinomas. The emerging role of molecular profiling may further refine therapeutic stratification in the coming decade.

doug b

If you’re feeling off-low energy, no sex drive, weird milk stuff-go get your prolactin checked. No excuses. It’s a simple blood test. Most docs will brush it off as stress or depression, but this? This is fixable. I’ve seen people go from feeling broken to having kids, traveling, living normal lives-all because they didn’t ignore the signs. Don’t be the guy who waits until he can’t see the side of the road to get help.

Rose Palmer

It is imperative to emphasize the necessity of longitudinal monitoring in patients receiving prolonged dopamine agonist therapy. While cabergoline demonstrates exceptional efficacy, the potential for valvular heart disease, particularly at cumulative weekly doses exceeding 2.5 mg, necessitates regular echocardiographic evaluation in accordance with European Society of Endocrinology guidelines. Furthermore, the psychological sequelae of hormonal dysregulation warrant integrated psychosocial support as a standard component of care.

Timothy Davis

Everyone’s acting like this is some miracle cure. Let’s be real-cabergoline makes you nauseous, dizzy, and sometimes hallucinates. And don’t even get me started on the people who think they can just stop taking it after a year. You think your pituitary is gonna magically reset? Nah. You’re gonna be on this for life, and you’ll thank me later when your prolactin spikes and your tumor comes back bigger than before. Also, your "success story" with pregnancy? That’s anecdotal. Real science says 70% relapse rate. Stop romanticizing this.

John Rose

It’s wild how much we take our hormones for granted until they stop working right. I had a cousin with this-she was diagnosed after three years of trying to get pregnant. She thought she was infertile. Turns out, her body was just flooded with milk hormones. Once she started cabergoline, she got pregnant within six months. It’s not just a tumor-it’s a whole life reset. I wish more people knew this was out there.

Amber Daugs

People are so careless with their health. If you’re leaking milk and not pregnant, that’s not "normal stress." That’s your body screaming for help. And if you’re a man and you’re tired all the time, don’t blame work-get tested. You’re not "just tired," you might have a brain tumor. And no, you can’t just take vitamins and hope it goes away. This isn’t a lifestyle blog. This is medicine. Get your act together.

Ambrose Curtis

just read this whole thing and wow. i had no idea prolactinomas were this common. i thought it was like, super rare. turns out i know like 3 people who had it and never knew. my bro had it and thought his boobs were from weight gain. took him 2 years to get tested. cabergoline saved his life literally. he’s got a kid now. also, the part about vision loss? yeah, that’s real. my aunt lost peripheral vision and thought she was just getting old. turns out her tumor was the size of a grape. got surgery, now she’s fine. but if she waited another year? she’d be blind. so if you’re weird symptoms? go get checked. it’s not a big deal. it’s a blood test. do it.